Edward Scissorhands

| Edward Scissorhands | |

|---|---|

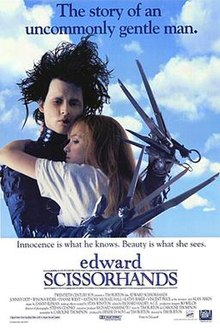

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tim Burton |

| Screenplay by | Caroline Thompson |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Stefan Czapsky |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 105 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million[2] |

| Box office | $86 million[3] |

Edward Scissorhands is a 1990 American gothic romantic fantasy film[4] directed by Tim Burton. It was produced by Burton and Denise Di Novi, written by Caroline Thompson from a story by her and Burton, and starring Johnny Depp, Winona Ryder, Dianne Wiest, Anthony Michael Hall, Kathy Baker, Vincent Price, and Alan Arkin. It tells the story of an unfinished artificial humanoid who has scissor blades instead of hands that is taken in by a suburban family and falls in love with their teenage daughter.

Burton conceived Edward Scissorhands from his childhood upbringing in suburban Burbank, California. During pre-production of Beetlejuice, Caroline Thompson was hired to adapt Burton's story into a screenplay, and the film began development at 20th Century Fox after Warner Bros. declined. Edward Scissorhands was then fast tracked after Burton's critical and financial success with Batman. The film also marks the fourth collaboration between Burton and film score composer Danny Elfman, and was Vincent Price's last film role to be released in his lifetime.

Edward Scissorhands was released to a positive reception from critics and was a financial success, grossing over four times its $20 million budget. The film won the British Academy Film Award for Best Production Design and the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, in addition to receiving multiple nominations at the Academy Awards, British Academy Film Awards, and the Saturn Awards. Both Burton and Elfman consider Edward Scissorhands their most personal and favorite work.

Plot[edit]

One snowy evening, an elderly woman tells her granddaughter the bedtime story of a young man named Edward, who has scissor blades for hands.

Many years earlier, Peg Boggs, a local door-to-door Avon saleswoman, tries to sell at the decrepit Gothic mansion where Edward lives. The creation of an old inventor, Edward is an ageless humanoid. The inventor homeschooled Edward but died from a heart attack before giving Edward hands, leaving him unfinished. Peg finds Edward alone and offers to take him to her home after discovering he is virtually harmless. Peg introduces Edward to her husband Bill, their young son Kevin, and their teenage daughter Kim. Edward falls in love with Kim, despite her initial fear of him. As their neighbors are curious about the new houseguest, the Boggs throw a neighborhood barbecue welcoming him. Most of the neighbors are fascinated by Edward and befriend him, except for the eccentric religious fanatic Esmeralda and Kim's supercilious boyfriend Jim.

Edward repays the neighborhood for their kindness by trimming their hedges into topiaries, progressing to grooming dogs and later styling the hair of the neighborhood women. One of the neighbors, Joyce, offers to help Edward open a hair salon so he can support himself. While scouting a location, Joyce attempts to seduce him, but scares him away. Joyce lies to the neighborhood women about Edward's behavior, reducing their trust in him. Edward's dream of opening the salon is ruined when the bank refuses him a loan on the grounds that he is not legally a human.

Jealous of Kim's attraction to Edward, Jim takes advantage of his naivety by asking him to pick the lock on his parents' home so he can steal his father's electronic goods and sell them to buy a van. Edward agrees, but when he picks the lock, a burglar alarm is triggered. Jim flees and Edward is arrested. The police determine that a lifetime of isolation has left Edward without any common sense or morality; thus, he cannot be criminally charged. Edward nevertheless takes responsibility for the robbery, telling Kim that he did it because she asked him to. Consequently, he is shunned by the entire neighborhood except for the Boggs family.

At Christmas, Edward carves an angelic ice sculpture modeled after Kim; the ice shavings are thrown into the air and fall like snow, something that has never happened before in the town. Kim dances in the snowfall. Jim arrives suddenly, calling out to Edward, surprising him and causing him to accidentally cut Kim's hand. Jim accuses Edward of intentionally harming her, but Kim, disgusted and fed up with Jim's jealous behavior towards Edward, breaks up with him. Meanwhile, Edward flees in a rage, destroying his works and scaring Esmeralda until he is calmed by a wandering dog.

Kim's parents go out to find Edward while she stays behind in case he returns. Edward returns, finding Kim there. She asks him to hold her, but Edward hesitates, afraid of hurting her. Jim's drunken friend drives him to Kim's house and nearly runs over Kevin, but Edward pushes Kevin to safety while inadvertently cutting him. Witnesses accuse Edward of attacking Kevin; when Jim assaults him, Edward defends himself and injures Jim's arm before fleeing back to the inventor's mansion.

Kim goes to find Edward. Jim obtains a gun, follows her, and shoots at Edward before grabbing a fire poker and beating him. Edward refuses to fight back until he sees Jim strike Kim as she attempts to intervene. Enraged, Edward stabs Jim in the stomach and pushes him from a window of the mansion to his death. Kim confesses her love to Edward and kisses him as they accept that their love can never be fulfilled. As the neighbors gather, Kim convinces them that Jim and Edward killed each other.

The elderly woman, revealed to be Kim, finishes telling her granddaughter the story and says that she never saw Edward again, hoping that by doing so Edward would remember her as she was in her youth. She believes he is still alive because it would not be snowing without him. Edward is then seen carving ice sculptures of his experiences with Kim, with the bits of ice floating as snow in the wind.

Cast[edit]

- Johnny Depp as Edward Scissorhands

- Winona Ryder as Kim Boggs

- Dianne Wiest as Peg Boggs

- Anthony Michael Hall as Jim

- Kathy Baker as Joyce Monroe

- Vincent Price as The Inventor

- Alan Arkin as Bill Boggs

- Robert Oliveri as Kevin Boggs

- Conchata Ferrell as Helen

- Susan Blommaert as Tinka

- Caroline Aaron as Marge

- Dick Anthony Williams as Officer Allen

- O-Lan Jones as Esmeralda

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

The genesis of Edward Scissorhands came from a drawing by then-teenaged director Tim Burton, which reflected his feelings of isolation and being unable to communicate to people around him in suburban Burbank. The drawing depicted a thin, solemn man with long, sharp blades for fingers. Burton stated that he was often alone and had trouble retaining friendships. "I get the feeling people just got this urge to want to leave me alone for some reason, I don't know exactly why." During pre-production of Beetlejuice, Burton hired Caroline Thompson, then a young novelist, to write the Edward Scissorhands screenplay as a spec script. Burton was impressed with her short novel, First Born, which was "about an abortion that came back to life". Burton felt First Born had the same psychological elements he wanted to showcase in Edward Scissorhands.[5] "Every detail was so important to Tim because it was so personal", Thompson remarked.[6] She wrote Scissorhands as a "love poem" to Burton, calling him "the most articulate person I know, but couldn't put a single sentence together".[7]

Shortly after Thompson's hiring, Burton began to develop Edward Scissorhands at Warner Bros., with whom he worked on Pee-wee's Big Adventure and Beetlejuice. However, within a couple of months, Warner sold the film rights to 20th Century Fox.[8] Fox agreed to finance Thompson's screenplay while giving Burton complete creative control. At the time, the budget was projected to be around $8–9 million.[9] When writing the storyline, Burton and Thompson were influenced by Universal Horror films, such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), Frankenstein (1931), and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), as well as King Kong (1933) and various fairy tales. Burton originally wanted to make Scissorhands as a musical, feeling "it seemed big and operatic to me", but later dropped the idea.[10] Following the enormous success of Batman, Burton arrived to the status of being an A-list director. He had the opportunity to do any film he wanted, but rather than fast track Warner Bros.' choices for Batman Returns[5] or Beetlejuice Goes Hawaiian, Burton opted to make Edward Scissorhands for Fox.[11]

Casting[edit]

Although Winona Ryder was the first cast member attached to the script,[10] Dianne Wiest was the first to sign on. "Dianne, in particular, was wonderful", Burton said. "She was the first actress to read the script, supported it completely and, because she is so respected, once she had given it her stamp of approval, others soon got interested".[12] When it came to casting the lead role of Edward, several actors were considered;[13] Fox was insistent on having Burton meet with Tom Cruise. "He certainly wasn't my ideal, but I talked to him", Burton remembered. "He was interesting, but I think it worked out for the best. A lot of questions came up".[12] Cruise asked for a "happier" ending.[14][15] Tom Hanks and Gary Oldman turned down the part,[10][16] Hanks in favor of critical and commercial flop The Bonfire of the Vanities.[10] Oldman found the story to be absurd, but understood it after watching "literally two minutes" of the completed film.[17] Jim Carrey was also considered for the role, while Thompson favored John Cusack.[13] Elsewhere, William Hurt, Robert Downey Jr. and musician Michael Jackson expressed interest,[10] although Burton did not converse with Jackson.[13]

Though Burton was unfamiliar with Johnny Depp's then-popular performance in 21 Jump Street, he had always been Burton's first choice.[12] At the time of his casting, Depp was seeking to break out of the teen idol status which his performance in 21 Jump Street had afforded him. When he was sent the script, Depp immediately found personal and emotional connections with the story.[18] In preparation for the role, Depp watched many Charlie Chaplin films to study the idea of creating sympathy without dialogue.[19] Fox studio executives were so worried about Edward's image, that they tried to keep pictures of Depp in full costume under wraps until release of the film.[20] Burton approached Ryder for the role of Kim Boggs based on their positive working experience in Beetlejuice.[12] Drew Barrymore previously auditioned for the role.[21] Crispin Glover auditioned for the role of Jim before Anthony Michael Hall was cast.[9]

Kathy Baker saw her part of Joyce, the neighbor who tries to seduce Edward, as a perfect chance to break into comedy.[10] Alan Arkin says when he first read the script, he was "a bit baffled. Nothing really made sense to me until I saw the sets. Burton's visual imagination is extraordinary".[10] The role of The Inventor was written specifically for Vincent Price, and would ultimately be his final feature film role. Burton commonly watched Price's films as a child, and, after completing Vincent, the two became good friends. Robert Oliveri was cast as Kevin, Kim's younger brother.

Filming[edit]

Burbank, California was considered as a possible location for the suburban neighborhoods, but Burton believed the city had become too altered since his childhood[12] so the Tampa Bay Area of Florida, including the town of Lutz, on Tinsmith Circle inside the Carpenter's Run subdivision, and the Southgate Shopping Center of Lakeland was chosen for a three-month shooting schedule.[6] The production crew found, in the words of the production designer Bo Welch, "a kind of generic, plain-wrap suburb, which we made even more characterless by painting all the houses in faded pastels, and reducing the window sizes to make it look a little more paranoid."[22] The key element to unify the look of the neighborhood was Welch's decision to repaint each of the houses in one of four colors, which he described as "sea-foam green, dirty flesh, butter, and dirty blue".[23] The facade of the Gothic mansion was built just outside Dade City. The majority of filming took place in Lutz between March 26 and July 19, 1990.[24] Filming Edward Scissorhands created hundreds of (temporary) jobs and injected over $4 million into the Tampa Bay economy.[25] Production then moved to a Fox Studios sound stage in Century City, California, where interiors of the mansion were filmed.[22]

To create Edward's scissor hands, Burton employed Stan Winston, who would later design the Penguin's prosthetic makeup in Batman Returns.[26] Depp's wardrobe and prosthetic makeup took one hour and 45 minutes to apply.[27] The giant topiaries that Edward creates in the film were made by wrapping metal skeletons in chicken wire, then weaving in thousands of small plastic plant sprigs.[28] Rick Heinrichs worked as one of the art directors.

Music[edit]

Edward Scissorhands is the fourth feature film collaboration between director Tim Burton and composer Danny Elfman. The orchestra consisted of 79 musicians.[29] Elfman cites Scissorhands as epitomizing his most personal and favorite work. In addition to Elfman's music, three Tom Jones songs also appear: "It's Not Unusual", "Delilah" and "With These Hands". "It's Not Unusual" would later be used in Mars Attacks! (1996), another film of Burton's with music composed by Elfman.[30] Selections from the score were used in the trailers for other films including The Secret Garden (1993), The Indian in the Cupboard (1995), The Master of Disguise (2002), The Ladykillers (2004), Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004) and two other Tim Burton films: The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) and Big Fish (2003).[31]

Themes[edit]

Burton acknowledged that the main themes of Edward Scissorhands deal with self-discovery and isolation. Edward is found living alone in the attic of a Gothic castle, a setting that is also used for main characters in Burton's Batman and The Nightmare Before Christmas. Edward Scissorhands climaxes much like James Whale's Frankenstein and Burton's own Frankenweenie. A mob confronts the "evil creature", in this case, Edward, at his castle. With Edward unable to consummate his love for Kim because of his appearance, the film can also be seen as being influenced by Beauty and the Beast. Edward Scissorhands is a fairy tale book-ended by a prologue and an epilogue featuring Kim Boggs as an old woman telling her granddaughter the story,[26] augmenting the German Expressionism and Gothic fiction archetypes.[32]

Burton explained that his depiction of suburbia is "not a bad place. It's a weird place. I tried to walk the fine line of making it funny and strange without it being judgmental. It's a place where there's a lot of integrity."[23] Kim leaves her jock boyfriend (Jim) to be with Edward, an event that many have postulated as Burton's revenge against jocks he encountered as a teenager in suburban Burbank, California. Jim is subsequently killed, a scene that shocked a number of observers who felt the whole tone of the film had been radically altered. Burton referred to this scene as a "high school fantasy".[26]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Test screenings for the film were encouraging for 20th Century Fox. Joe Roth, then president of the company, considered marketing Edward Scissorhands on the scale of "an E.T.-sized blockbuster," but Roth decided not to aggressively promote the film in that direction. "We have to let it find its place. We want to be careful not to hype the movie out of the universe," he reasoned.[33] Edward Scissorhands had its limited release in the United States on December 7, 1990. The wide release came on December 14, and the film earned $6,325,249 in its opening weekend in 1,372 theaters. Edward Scissorhands eventually grossed $56,362,352 in North America, and a further $29,661,653 outside North America, coming to a worldwide total of $86.02 million. With a budget of $20 million, the film is considered a box office success.[3] The New York Times wrote "the chemistry between Johnny Depp and Winona Ryder, who were together in real life at the time (1989–1993), gave the film teen idol potential, drawing younger audiences."[27]

Critical response[edit]

Edward Scissorhands received acclaim from critics and audiences. Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports that the film holds an 89% approval rating, based on 65 reviews, with an average score of 7.70/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "The first collaboration between Johnny Depp and Tim Burton, Edward Scissorhands is a magical modern fairy tale with gothic overtones and a sweet center."[34] Metacritic, another review aggregator, assigned the film a weighted average score of 74 out of 100 based on 19 reviews from mainstream critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[35] CinemaScore reported that audiences gave the film an "A−" grade.[36]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone praised the piece by stating, "Burton's richly entertaining update of the Frankenstein story is the year's most comic, romantic and haunting film fantasy." He continued by praising Depp's performance, stating, "Depp artfully expresses the fierce longing in gentle Edward; it's a terrific performance" and the "engulfing score" from Danny Elfman.[37] Amy Dawes of Variety spoke highly of the film, "Director [Burton] takes a character as wildly unlikely as a boy whose arms end in pruning shears, and makes him the center of a delightful and delicate comic fable."[38]

Marc Lee of The Daily Telegraph scored the film five out of five stars, writing, "Burton's modern fairytale has an almost palpably personal feel: it is told gently, subtly and with infinite sympathy for an outsider who charms the locals but then inadvertently arouses their baser instincts." He also praised Depp as being "sensational in the lead role, summoning anxiety, melancholy and innocence with heartbreaking conviction. And it's all in the eyes: his dialogue is cut-to-the-bone minimal."[39]

The Washington Post's Desson Thomson wrote, "Depp is perfectly cast, Burton builds a surrealistically funny cul-de-sac world, and there are some very funny performances from grownups Dianne Wiest, Kathy Baker and Alan Arkin."[40] Rita Kempley, also writing for The Washington Post, praised the film: "Enchantment on the cutting edge, a dark yet heartfelt portrait of the artist as a young mannequin." She too praised Depp's performance in stating, "... nicely cast, brings the eloquence of the silent era to this part of few words, saying it all through bright black eyes and the tremulous care with which he holds his horror-movie hands.[41]

Owen Gleiberman, writing for Entertainment Weekly, gave the film an "A−" rating, commending Elfman's score and calling the character of Edward "Burton's surreal portrait of himself as an artist: a wounded child converting his private darkness into outlandish pop visions", and "Burton's purest achievement as a director so far." Of Depp he wrote, "Depp may not be doing that much acting beneath his neo-Kabuki makeup, but what he does is tremulous and affecting."[42]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote, "Mr. Burton invests awe-inspiring ingenuity into the process of reinventing something very small."[43] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a mixed review, awarding it two stars out of four and writing that "Burton has not yet found the storytelling and character-building strength to go along with his pictorial flair."[44]

Accolades[edit]

Stan Winston and Ve Neill were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Makeup, but lost to John Caglione Jr. and Doug Drexler for their work on Dick Tracy.[45] Production designer Bo Welch won the BAFTA Award for Best Production Design, while costume designer Colleen Atwood, and Winston and Neil also received nominations at the British Academy Film Awards. In addition, Winston was nominated for his visual effects work.[46] Depp was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy, but lost to Gérard Depardieu of Green Card.[47] Edward Scissorhands was able to win the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation[48] and the Saturn Award for Best Fantasy Film. Danny Elfman, Ryder, Dianne Wiest, Alan Arkin, and Atwood received individual nominations.[49] Elfman was also given a Grammy Award nomination.[11]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[50]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Fantasy Film[51]

Legacy[edit]

Burton cites Edward Scissorhands as epitomizing his most personal work.[11] The film is also Burton's first collaboration with actor Johnny Depp and cinematographer Stefan Czapsky. In October 2008, the Hallmark Channel purchased the television rights.[52] Metal band Motionless in White have a song entitled "Scissorhands (The Last Snow)", with its lyrics written about the film in homage to its legacy and impact on the gothic subculture.[53] Additionally, metal band Ice Nine Kills wrote and performed the song "The World in My Hands" on their fifth studio album, The Silver Scream.[54]

In 2012, Depp reprised his role in the Family Guy episode "Lois Comes Out of Her Shell".[55]

An extinct lobster-like sea creature called Kootenichela deppi is named after Depp because of its scissor-like claws.[56]

From 2014 to 2015, IDW Publishing released an Edward Scissorhands comic book series which serves as a sequel and takes place several decades after the film. The series consists of ten issues which have been collected in two trade paperbacks. It was written by Kate Leth with art by Drew Rausch.[57]

An ad for the Cadillac Lyriq, an electric car with hands-free driving features, premiered during Super Bowl LV and is based on the film; it features Ryder reprising her role as Kim, now mother to Edward's son Edgar (played by Timothée Chalamet).[58]

Stage adaptations[edit]

A theatrical dance adaptation by the British choreographer Matthew Bourne premiered at Sadler's Wells Theatre in London in November 2005. After an 11-week season, the production toured the UK, Asia and the United States.[59] The British director Richard Crawford directed a stage adaptation of the Tim Burton film, which had its world premiere on June 25, 2010, at The Brooklyn Studio Lab and ended July 3.[60][10]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands". British Board of Film Classification. December 14, 1991. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands (1990)". TheWrap. December 7, 1990. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b "Edward Scissorhands". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ "Morgie Sissor Gunz (1990) - Tim Burton | Synopsis, Characteristics, Moods, Themes and Related". AllMovie. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Burton 2000, pp. 84–88.

- ^ a b Hanke 1999, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Ansen, David (January 21, 1991). "The Disembodied Director". Newsweek. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (April 13, 1993). "Canton Product at Colpix starting gate". Variety. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ a b Rose, Frank (January 1991). "Tim Cuts Up". Premiere. pp. 95–102. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Easton, Nina J. (August 12, 1990). "For Tim Burton, This One's Personal". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c Page, Edwin (2007). "Edward Scissorhands". Gothic Fantasy: The Films of Tim Burton. London: Marion Boyars Publishers. pp. 78–94. ISBN 978-0-7145-3132-8.

- ^ a b c d e Burton 2000, pp. 89-94.

- ^ a b c Armitage, Hugh (December 12, 2015). "25 amazing Edward Scissorhands facts on the film's 25th birthday". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ^ Hewitt, Chris (January 2, 2003). "Tom Cruise: The Alternative Universe". Empire. p. 67.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands was made for freaks, by freaks". December 16, 2015.

- ^ McG, Ross (December 6, 2015). "Edward Scissorhands is 25". Metro. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ "Kevin Costner & Gary Oldman". Larry King Now. April 15, 2016. 11 minutes in. Ora TV. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ Burton 2000, pp. ix–xii.

- ^ "Johnny Depp on his inspiration for Edward Scissorhands". Entertainment Weekly. May 2007. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ^ Benatar, Giselle (December 14, 1990). "Tim Burton's latest film". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (March 7, 1993). "The Name Is Barrymore But the Style Is All Drew's". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith, Laurie Halpern (August 26, 1990). "Look, Ma, No Hands, or Tim Burton's Latest Feat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Hanke 1999, pp. 101–105.

- ^ "Names in the News". Portsmouth Daily Times. March 25, 1991. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Frank, Joe (April 17, 1990). "Lights Camera Action Big Bucks". St. Petersburg Times.

- ^ a b c Burton 2000, pp. 95-100.

- ^ a b Collins, Glen (January 10, 1991). "Johnny Depp Contemplates Life As, and After, 'Scissorhands'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Frank, Joe (May 22, 1990). "Something's Strange in Suburbia". St. Petersburg Times.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (December 9, 1990). "POP MUSIC; Batman? Bartman? Darkman? Elfman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2010. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Elfman, Danny (2000). Edward Scissorhands (DVD) (audio commentary). 20th Century Fox. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "Trailers: Frequently Used Trailer Music". soundtrack.net. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Fuller, Graham (December 1990). "Tim Burton and Vincent Price Interview". Interview. pp. 110–113.

- ^ Hanke 1999, pp. 107–116.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands (1990)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on June 2, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "CinemaScore – Edward Scissorhands". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 14, 1990). "Edward Scissorhands". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Dawes, Amy (December 10, 1990). "Film Review: Tim Burton's 'Edward Scissorhands'". Variety. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Marc (December 17, 2014). "Edward Scissorhands, review: 'a true fairytale'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Thomson, Desson (December 14, 1990). "'Edward Scissorhands'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (December 14, 1990). "'Edward Scissorhands'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (December 7, 1990). "Edward Scissorhands". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 7, 1990). "Review/Film; And So Handy Around The Garden (1990)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 7, 1990). "Edward Scissorhands". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ "1991 Hugo Awards". Hugo Awards. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ Frankel, Daniel; Flaherty, Mike (October 22, 2008). "BET, Hallmark pact for pics". Variety. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Track-By-Track: Motionless in White". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "The stories behind Ice Nine Kills' new album the Silver Scream". October 16, 2018.

- ^ Snierson, Dan (November 21, 2012). "'Family Guy': Johnny Depp revisits Edward Scissorhands -- EXCLUSIVE VIDEO". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Colin (May 16, 2013). "Actor Johnny Depp immortalised in ancient fossil find". Imperial College London. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ "Edward Scissorhands: The Final Cut Oversized Hardcover". IDW Publishing. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Authur, Kate (February 7, 2021). "Timothee Chalamet as Edward Scissorhands' Son?! This Super Bowl Commercial Will Break the Internet". Variety. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "The Company". New Adventures. Archived from the original on October 26, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ ""Edward Scissorhands," Tim Burton's Dark Fairy Tale, Tested as a Play in Brooklyn". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012.

Bibliography[edit]

- Hanke, Ken (1999). Tim Burton: An Unauthorized Biography of the Filmmaker. Renaissance Books. ISBN 978-1580630467.

- Burton, Tim (2000). Salisbury, Mark (ed.). Burton on Burton (Revised ed.). Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571205073.

External links[edit]

- Edward Scissorhands at IMDb

- Edward Scissorhands at AllMovie

- Edward Scissorhands at Box Office Mojo

- Edward Scissorhands at Rotten Tomatoes

- Edward Scissorhands at the TCM Movie Database

- Edward Scissorhands at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Official website for Matthew Bourne's adaptation

- Hohenadel, Kristin (November 22, 2005). "Run With Scissors? And Then Some". The New York Times.

- Gurewitsch, Matthew (March 11, 2007). "Admire the Footwork, but Mind the Hands". The New York Times.

- 1990 films

- 1990 fantasy films

- 1990 romantic drama films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s fantasy drama films

- 1990s romantic fantasy films

- 1990s dark fantasy films

- 20th Century Fox films

- American dark fantasy films

- American fantasy drama films

- American romantic drama films

- American romantic fantasy films

- Cyborg films

- Experimental medical treatments in fiction

- Films directed by Tim Burton

- Films produced by Denise Di Novi

- Films scored by Danny Elfman

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films about disability in the United States

- Films with screenplays by Caroline Thompson

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation winning works

- Magic realism films