Classic rock

Classic rock is a radio format that developed from the album-oriented rock (AOR) format in the early 1980s.[2] In the United States, it comprises rock music ranging generally from the mid-1960s through the mid-1990s,[3][a] primarily focusing on commercially successful blues rock and hard rock popularized in the 1970s AOR format.[2] The radio format became increasingly popular with the baby boomer demographic by the end of the 1990s.[5]

Although classic rock has mostly appealed to adult listeners, music associated with this format received more exposure with younger listeners with the presence of the Internet and digital downloading.[6] Some classic rock stations also play a limited number of current releases which are stylistically consistent with the station's sound, or by heritage acts which are still active and producing new music.[7]

Among academics and historians, classic rock has been discussed as an effort by critics, media, and music establishments to canonize rock music and commodify 1960s Western culture for audiences living in a post-baby boomer economy. The music selected for the format has been identified as predominantly commercially successful songs by white male acts from the Anglosphere, expressing values of Romanticism, self-aggrandizement, and politically undemanding ideologies. It has been associated with the album era (1960s–2000s), particularly the period's early pop/rock music.

History[edit]

The classic rock format evolved from AOR radio stations that were attempting to appeal to an older audience by including familiar songs of the past with current hits.[8] In 1980, AOR radio station M105 in Cleveland began billing itself as "Cleveland's Classic Rock", playing a mix of rock music from the mid-1960s to the present.[9] Similarly, WMET called itself "Chicago's Classic Rock" in 1981.[10] In 1982, radio consultant Lee Abrams developed the "Timeless Rock" format which combined contemporary AOR with rock hits from the 1960s and 1970s.[11]

KRBE, an AM station in Houston, was an early classic rock radio station. In 1983 program director Paul Christy designed a format which played only early album rock, from the 1960s and early 1970s, without current music or any titles from the pop or dance side of Top 40.[12] Another AM station airing classic rock, beginning in 1983, was KRQX in Dallas-Fort Worth.[13] KRQX was co-owned with an album rock station, 97.9 KZEW. Management saw the benefit in the FM station appealing to younger rock fans and the AM station appealing a bit older. The ratings of both stations could be added together to appeal to advertisers. Classic rock soon became the widely used descriptor for the format and became the commonly used term among the general public for early album rock music.

In the mid-1980s, the format's widespread proliferation came on the heels of Jacobs Media's (Fred Jacobs) success at WCXR, in Washington, D.C., and Edinborough Rand's (Gary Guthrie) success at WZLX in Boston. Between Guthrie and Jacobs, they converted more than 40 major market radio stations to their individual brand of classic rock over the next several years.[14]

Billboard magazine's Kim Freeman posits that "while classic rock's origins can be traced back earlier, 1986 is generally cited as the year of its birth".[15] By 1986, the success of the format resulted in oldies accounting for 60–80% of the music played on album rock stations.[16] Although it began as a niche format spun off from AOR, by 2001 classic rock had surpassed album rock in market share nationally.[17]

During the mid-1980s, the classic rock format was mainly tailored to the adult male demographic ages 25–34, which remained its largest demographic through the mid-1990s.[18] As the format's audience aged, its demographics skewed toward older age groups. By 2006, the 35–44 age group was the format's largest audience[19] and by 2014 the 45–54 year-old demographic was the largest.[20]

Programming[edit]

Typically, classic rock stations play rock songs from the mid-1960s through the 1980s and began adding 1990s music in the early 2010s. Most recently there has been a "newer classic rock" under the slogan of the next generation of classic rock. Stations such as WLLZ in Detroit, WBOS in Boston, and WKQQ in Lexington play music focusing more on harder edge classic rock from the 1980s to the 2000s.[21][22][23]

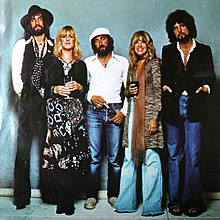

Some of the artists that are featured heavily on classic rock radio are the Beatles,[24] Pink Floyd, Genesis, Aerosmith, AC/DC, Quiet Riot, Bruce Springsteen, John Mellencamp, Def Leppard, Boston, the Cars, Fleetwood Mac, Billy Joel, Elton John, Bryan Adams, Eric Clapton, the Who, Van Halen, Rush, Black Sabbath, U2, Guns N' Roses, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Eagles, the Doors, Styx,[25] Queen, Led Zeppelin,[26] and Jimi Hendrix.[26] The songs of the Rolling Stones, particularly from the 1970s, have become staples of classic rock radio.[27] "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" (1965),[28] "Under My Thumb" (1966),[29] "Paint It Black" (1966),[30] and "Miss You" (1978) are among their most popular selections, with Complex calling the latter "an eternal mainstay on classic-rock radio".[31]

A 2006 Rolling Stone article noted that teens were surprisingly interested in classic rock and speculated that the interest in the older bands might be related to the absence of any new, dominant sounds in rock music since the advent of grunge.[26]

Characteristics and academic response[edit]

Ideologically, 'classic rock' serves to confirm the dominant status of a particular period of music history – the emergence of rock in the mid-1960s – with its associated values and set of practices: live performance, self-expression, and authenticity; the group as the creative unit, with the charismatic lead singer playing a key role, and the guitar as the primary instrument. This was a version of classic Romanticism, an ideology with its origins in art and aesthetics.

— Roy Shuker (2016)[32]

Classic-rock radio programmers largely play "tried and proven" hit songs from the past based on their "high listener recognition and identification", says media academic Roy Shuker, who also identifies white male rock acts from Sgt. Pepper-era Beatles through the late 1970s as the focus of their playlists.[32] As Catherine Strong observes, classic rock songs are generally performed by white male acts from either the United States or the United Kingdom, "have a four-four time, very rarely exceed the time limit of four minutes, were composed by the musicians themselves, are sung in English, played by a 'classical' rock formation (drums, bass, guitar, keyboard instruments) and were released on a major label after 1964."[33] Classic rock has also been associated with the album era (1960s–2000s), by writers Bob Lefsetz[34] and Matthew Restall, who says the term is a relabeling of the "virtuoso pop/rock" from the era's early decades.[35]

The format's origins are traced by music scholar Jon Stratton to the emergence of a classic-rock canon.[36] This canon arose in part from music journalism and superlative lists ranking certain albums and songs that are consequently reinforced to the collective and public memory.[33] Robert Christgau says the classic-rock concept transmogrified rock music into a "myth of rock as art-that-stands-the-test-of-time". He also believes it was inevitable that certain rock artists would be canonized by critics, major media, and music establishment entities such as the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[37] In 2018, Steven Hyden recalls how the appearance of classic rock as a timeless music lent it a distinction from the "inherently nihilistic" pop he had first listened to on the radio as a teenager in the early 1990s. "[I]t seemed to have been around forever," he writes of the classic rock format. "It was there long before I was born, and I was sure it was still going to be around after I was gone."[38]

Politically, the mindset underlying classic rock is regarded by Christgau as regressive. He says the music in this format abandoned ironic sensibilities in favor of unintellectual, conventional aesthetics rooted in Victorian era Romanticism, while downplaying the more radical aspects of 1960s counterculture, such as politics, race, African-American music, and pop in the art sense. "Though classic rock draws its inspiration and most of its heroes from the '60s, it is, of course, a construction of the '70s," he writes in 1991 for Details magazine. "It was invented by prepunk/predisco radio programmers who knew that before they could totally commodify '60s culture they'd have to rework it—that is, selectively distort it till it threatened no one ... In the official rock pantheon the Doors and Led Zeppelin are Great Artists while Chuck Berry and Little Richard are Primitive Forefathers and James Brown and Sly Stone are Something Else."[37]

Regarding the relationship of economics to the rise of classic rock, Christgau believes there was compromised socioeconomic security and diminishing collective consciousness of a new generation of listeners in the 1970s, who succeeded rock's early years during baby-boomer economic prosperity in the United States: "Not for nothing did classic rock crown the Doors' mystagogic middlebrow escapism and Led Zep's chest-thumping megalomaniac grandeur. Rhetorical self-aggrandizement that made no demands on everyday life was exactly what the times called for."[37] Shuker attributes the rise of classic-rock radio in part to "the consumer power of the aging post-war 'baby boomers' and the appeal of this group to radio advertisers". In his opinion, classic rock also produced a rock music ideology and discussion of the music that was "heavily gendered", celebrating "a male homosocial paradigm of musicianship" that "continued to dominate subsequent discourse, not just around rock music, but of popular music more generally."[32]

See also[edit]

- Active rock

- Classic alternative

- Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies

- Mainstream rock

- Music radio

- Rockism and poptimism

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Schube, Will (2021). "40 Bands That Define "Dad Rock"". spin.com.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon (June 18, 1986). "Oldies on Rise in Album-Rock Radio". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Hickey, Walt (July 8, 2014). "Classic Rock Started with the Beatles and Ended with Nirvana". fivethirtyeight.com. ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Akinfenwa, Jumi (September 14, 2020). "The Rolling Stones, Springsteen ... The Killers: what actually is 'classic rock'?". The Guardian. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ Leigh, Frederic A. (2011). "Classic Rock Format". In Sterling, Christopher H.; O'Dell, Cary (eds.). The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-1135176846. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ^ Kids are listening to their parents - Their parents' music, that is Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine USA Today March 30, 2004

- ^ "New York Radio Guide: Radio Format Guide", NYRadioGuide.com, 2009-01-12, webpage: NYRadio-formats. Archived March 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hill, Douglas. "AOR Nears Crucial Crossroads: Demographics, Ad Pressures My Force Fragmentation" Billboard May 22, 1982: 1

- ^ Scott, Jane. "The Happening" The Plain Dealer June 13, 1980: Friday 30

- ^ The Museum of Classic Chicago Television (www.FuzzyMemories.TV) (October 27, 2007). "WMET 95 and a Half FM (Commercial, 1981)". Archived from the original on October 11, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Timeless Rock FM Format Is Taking Shape", Billboard November 6, 1982: 1

- ^ Kojan, Harvey. "KRBE: Classic Pioneer" Radio & Records July 13, 1990: 47

- ^ "Broadcasting Yearbook 1984 page B-247" (PDF). americanradiohistory.com.

- ^ Freeman, Kim. "Classic Rock Thrives In 18 Months" Billboard October 25, 1986: 10

- ^ Kim Freeman. "Labels Fight Losing Battle vs. Classic Rock". Billboard. Vol. 99, No. 52. (December 26, 1987.) p. 88. Retrieved October 15, 2015. ISSN 0006-2510

- ^ "Overview 1986" Billboard December 27, 1986: Y4

- ^ Ross, Sean. "Classic Rock Overtakes Album In Spring Arbs" Billboard September 15, 2001: 75

- ^ Stark, Phyllis. "Katz Study Charts Classic Rock's Growth" Billboard July 16, 1994: 80

- ^ "What they're listening to on the radio". sportsbusinessdaily.com. American City Business Journals. June 26, 2006. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "WHY RADIO FACT SHEET". rab.com. Radio Advertising Bureau. 2014. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "WLLZ, Detroit's Wheels, rocks the airwaves again|Arts & Entertainment|theoaklandpress.com". Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "105.7 switches from sports to classic rock - The Columbis Dispatch". Archived from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ WBOS/Boston Flips From Alternative To 'Rock 92.9, The 'Next Generation Of Classic Rock'

- ^ "Top 1043 Songs of All Time - Q104.3".

- ^ "Styx". Billboard. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hiatt, Brian (February 23, 2006). "Rock and Roll: Classic Rock, Forever Young". Rolling Stone. No. 994. pp. 11–12. ProQuest 1197423.

- ^ Grow, Kory (April 18, 2019). "Rolling Stones Show Off Latter-Day Hits, Triumphant Live Performances on 'Honk'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Nealon, Jeffery (2012). Post-Postmodernism: or, The Cultural Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism. Stanford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0804783217.

- ^ Beviglia, Jim (2015). Counting Down the Rolling Stones: Their 100 Finest Songs. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 158. ISBN 978-1442254473.

- ^ DeBord, Matthew (October 20, 2016). "Tesla picked an odd Rolling Stones song for its latest Autopilot video". Business Insider. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Anon. (July 12, 2012). "The 50 Best Rolling Stones Songs". Complex. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Shuker, Roy (2016). Understanding Popular Music Culture (5th ed.). Routledge. pp. 141–2. ISBN 978-1317440895.

- ^ a b Strong, Catherine (2015). "Shaping the Past of Popular Music: Memory, Forgetting and Documenting". In Bennett, Andy; Waksman, Steve (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music. SAGE. p. 423. ISBN 978-1473910997.

- ^ Lefsetz, Bob (September 12, 2013). "Classic Rock's Era of the Album Gives Way to Today's Track Stars". Variety. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Restall, Matthew (2020). "5) A Few Surprises". Elton John's Blue Moves. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781501355431.

- ^ Stratton, Jon (2016). Britpop and the English Music Tradition. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-1317171225.

- ^ a b c Christgau, Robert (July 1991). "Classic Rock". Details. Archived from the original on June 4, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (2018). Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic Rock. Dey Street. p. 19. ISBN 9780062657121.