Chet Baker

Chet Baker | |

|---|---|

Baker in 1983 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Chesney Henry Baker Jr. |

| Born | December 23, 1929 Yale, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Died | May 13, 1988 (aged 58) Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1949–1988[1] |

| Labels | |

| Spouse(s) | Charlaine Souder

(m. 1950, divorced)Halema Alli

(m. 1956; div. 1964)Carol Ann Jackson (m. 1964) |

| Partner(s) |

|

Chesney Henry "Chet" Baker Jr. (December 23, 1929 – May 13, 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter and vocalist. He is known for major innovations in cool jazz that led him to be nicknamed the "Prince of Cool".[2]

Baker earned much attention and critical praise through the 1950s, particularly for albums featuring his vocals: Chet Baker Sings (1954) and It Could Happen to You (1958). Jazz historian Dave Gelly described the promise of Baker's early career as "James Dean, Sinatra, and Bix, rolled into one".[3] His well-publicized drug habit also drove his notoriety and fame. Baker was in and out of jail frequently before enjoying a career resurgence in the late 1970s and 1980s.[4]

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Baker was born December 23, 1929, in Yale, Oklahoma, and raised in a musical household.[5]: 169 His father, Chesney Baker Sr., was a professional Western swing guitarist, and his mother, Vera Moser, was a pianist who worked in a perfume factory. His maternal grandmother was Norwegian.[6]: 10 Baker said that owing to the Great Depression, his father, though talented, had to quit as a musician and take a regular job. In 1940, when Baker was 10, his family relocated to Glendale, California.[7]

Baker began his musical career singing in a church choir. His father, a fan of Jack Teagarden, gave him a trombone, before switching to the trumpet at the age of 13 when the trombone proved to be too large for him.[8] His mother said that he had begun to memorize tunes on the radio before he was given an instrument.[9] After "falling in love" with the trumpet, he improved noticeably in two weeks. Peers called Baker a natural musician to whom playing came effortlessly.[9]

Baker received some musical education at Glendale High School, but he left school at the age of 16 in 1946 to join the United States Army. He was assigned to Berlin, Germany, where he joined the 298th Army Band.[5]: 170 While stationed in Berlin, he became acquainted with modern jazz by listening to V-Discs of Dizzy Gillespie and Stan Kenton.[8] After leaving the Army in 1948, he studied music theory and harmony at El Camino College in Los Angeles.[10] He dropped out during his second year to re-enlist. He became a member of the Sixth Army Band at the Presidio in San Francisco,[10] spending time in clubs such as Bop City and the Black Hawk.[11] He was discharged from the Army in 1951 and proceeded to pursue a career in music.[12]

Career[edit]

Baker performed with Vido Musso and Stan Getz before being chosen by Charlie Parker for a series of West Coast engagements.[13]

In 1952, Baker joined the Gerry Mulligan Quartet and attracted considerable attention. Rather than playing identical melody lines in unison like Parker and Gillespie, Baker and Mulligan complemented each other with counterpoint and anticipating what the other would play next. "My Funny Valentine," with a solo by Baker, became a hit and was associated with Baker for the rest of his career.[14] With the quartet, Baker was a regular performer at Los Angeles jazz clubs such as The Haig and the Tiffany Club.[9]

In 1953, Mulligan was arrested and imprisoned on drug charges.

Baker formed a quartet with a rotation that included pianist Russ Freeman, bassists Bob Whitlock, Carson Smith, Joe Mondragon, and Jimmy Bond, and drummers Larry Bunker, Bob Neel, and Shelly Manne.

Baker's quartet released popular albums between 1953 and 1956. Baker won reader's polls at Metronome and DownBeat magazines, beating trumpeters Miles Davis and Clifford Brown. In 1954, readers named Baker the top jazz vocalist. In 1954, Pacific Jazz Records released Chet Baker Sings, an album that both increased his visibility and drew criticism. Nevertheless, Baker continued to sing throughout the rest of his career.

Baker, with his youthful, chiseled looks oft-photographed by William Claxton, and his cool demeanor that evoked breezy California playboy living, became somewhat of a teen idol on top of being a respected, up-and-coming jazz musician.[9] Hollywood studios saw movie star potential in Baker, and he made his acting debut in the film Hell's Horizon in the fall of 1955. Baker declined a studio contract, preferring life on the road as a musician.

Over the next few years, he led his own combos, including a 1955 quintet with Francy Boland where Baker combined trumpet-playing and singing. In September 1955, he left for Europe for the first time, completing an eight-month tour and recording for the Barclay label that October. Some of these sessions were released in the United States as Chet Baker in Europe.[15] While there, he also recorded a rare accompaniment for another vocalist: Caterina Valente playing guitar and singing "I'll Remember April" and "Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye".[16]

One month into the tour, pianist Dick Twardzik died of a heroin overdose. Despite this, Baker continued the tour, employing local pianists.[16]

Returning to Los Angeles post-tour, Baker returned to recording for Pacific Jazz. His output included three collaborations with Art Pepper, including Playboys, and the soundtrack to The James Dean Story. Baker moved to New York City, where he collaborated again with Gerry Mulligan for the 1957 release Reunion with Chet Baker. In 1958, Baker rejoined with Stan Getz for Stan Meets Chet. That same year, he also released It Could Happen to You, similar to Chet Baker Sings, notable for featuring his scat singing skills in lieu of trumpet-playing. His last significant release before returning to Europe was Chet, released by Riverside Records, featuring an all-star personnel that included pianist Bill Evans, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones, all associated with leading jazz trumpeter Miles Davis.

Drug addiction and decline[edit]

Soon after signing on with Riverside Records, Baker was arrested twice; the first arrest involving a stay at a Lexington hospital, then imprisonment at Rikers Island for four months on drug charges. Baker said he began using heroin in 1957.[5]: 191 However, author Jeroen de Valk and pianist Russ Freeman said that Baker started heroin in the early 1950s. Freeman was Baker's musical director after Baker left the Mulligan quartet. Sometimes Baker pawned his instruments to buy drugs.

In late 1959, Baker returned to Europe, recording in Italy what became known as the Milano sessions with arranger and conductor Ezio Leoni (Len Mercer) and his orchestra. Baker appeared as himself in the musicarello film, Howlers in the Dock. Tabloids reviled Baker for his drug habit and reckless womanizing and infidelity.[6]: 169–170 In August 1960, he was imprisoned in Lucca for importing narcotics, forging prescriptions, and drug abuse.[5]: 191 [17] This forced Leoni to communicate through the prison warden to coordinate arrangements with Baker as they prepared for recording.[18]

Baker spent more than a year in jail, and was later expelled from Germany and the UK on drug-related offenses. He was deported to the U.S. from Germany for getting into trouble with the law a second time. He settled in Milpitas, California, performing in San Francisco and San Jose between jail terms for prescription fraud.[1]

Baker's first release in 1962, after his Italian prison sentence, was Chet Is Back! for RCA, balancing ballads with energetic bop. That same year, Baker collaborated with Ennio Morricone in Rome for a series of orchestral pop records, recording four original songs that he had composed during his prison sentence: "Chetty's Lullaby", "So che ti perderò", "Motivo su raggio di luna", and "Il mio domani".[17]

Baker returned to New York City in 1964.[19] Throughout most of the 1960s, Baker played flugelhorn, and recorded music that could be classified as West Coast jazz.[1] In 1964, he released The Most Important Jazz Album of 1964/65 on Colpix Records, and in 1965 he released Baby Breeze on Limelight. He then released five albums with Prestige, recorded in one week.[20]

Baker fell behind on jazz's latest innovations.[8]: 96 At the end of 1965, he returned to the Pacific label, recording six themed albums whose content veered from straight jazz towards uninspired, instrumental covers of contemporary pop songs arranged by Bud Shank. Baker himself was unhappy with the records, describing them as "simply a job to pay the rent." By this time, he had a wife and three children to support.[8]: 100–101

That summer, already having reached a low point in his career, Baker was beaten, probably while attempting to buy drugs,[21] after performing at The Trident in Sausalito. In the film Let's Get Lost, Baker said an acquaintance attempted to rob him, but backed off, only to return the next night with a group of men who chased him. He entered a car and was surrounded. Instead of rescuing him, the people inside the car pushed him back out onto the street, where the chase continued. He received cuts and several of his teeth were knocked out. This incident has been often misdated or otherwise said to be exaggerated partly because of his own unreliable testimony on the matter.[1][9]

Regardless, the 1966 incident did lead to his teeth eventually deteriorating. By late 1968 or early 1969, he needed dentures.[8] This ruined his embouchure, and he struggled to relearn how to play the trumpet and flugelhorn.

Baker claims that, for three years, he worked at a gas station until concluding that he had to find a way back to music and retrain his embouchure.[22] Biographer Jeroen de Valk notes that Baker was still musically active after 1966, performing and occasionally recording. In April 1968, he provided flugelhorn for Bud Shank's Magical Mystery album.[8] In 1969, he released Albert's House, which features 11 compositions by Steve Allen, who organized the recording date to help Baker restart his career. In 1970, Baker released Blood, Chet and Tears.

After these unsuccessful releases, Baker withdrew from the music business. He did not release another album for 4 years, and from around 1968 to 1973, stopped performing in public.[8] Moving back with his family to his mother's house in San Jose and depending on welfare, Baker was arrested for forging heroin prescriptions. The judge released him on the condition that he remained on methadone for the next seven years.[8]

Comeback[edit]

In 1973, Baker decided to attempt a comeback. Returning to the straight-ahead jazz that began his career, he drove to New York to perform again.[8] In 1974, the India Navigation label released a live album of performances with saxophonist Lee Konitz. She Was Too Good to Me, released by CTI Records that same year, is considered a comeback album. His last release of 1974 was another live album recorded at Carnegie Hall, which was his final collaboration with Gerry Mulligan.

From that time, work in both the U.S. and Europe was inconsistent. In 1977, Baker recorded Once Upon a Summertime and You Can't Go Home Again. That November, he returned to Europe to tour for the rest of that year. Being met with renewed interest in France, Italy, Germany, and Denmark, Baker decided to stay.[8] He worked almost exclusively in Europe, only returning to the U.S. about once a year to attend some performances.[23]

From that point on, Baker recorded a prolific amount of material. In 1979, Baker made 11 records; the following year, he made 10. They were released by small jazz labels such as Circle, SteepleChase, and Sandra.

During the early 1980s, Baker began to associate himself with musicians with whom he meshed well, such as guitarist Philip Catherine, bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, and pianist Michel Graillier.

Later in his career, Baker preferred to play in ensembles without drums.[8][24] He detested playing at loud venues to inattentive audiences. At gigs in lively French and American clubs, he would sometimes wait for over half an hour for noise to die down before beginning to perform, and he would pause his performance if the audience made a racket.[9][25]: 102

In 1983, British singer Elvis Costello, a longtime fan of Baker, hired the trumpeter to play a solo on his song "Shipbuilding" for the album Punch the Clock. The song exposed Baker's music to a new audience. Later, Baker often featured Costello's song "Almost Blue" (in turn inspired by Baker's version of "The Thrill Is Gone") in his concert sets.

In 1986, Chet Baker: Live at Ronnie Scott's London presented Baker in an intimate stage performance filmed with Elvis Costello and Van Morrison as he performed a set of standards and classics, including "Just Friends", "My Ideal", and "Shifting Down". Augmenting the music, Baker spoke one-on-one with friend and colleague Costello about his childhood, career, and struggle with drugs.

Baker recorded the live album Chet Baker in Tokyo with his quartet featuring pianist Harold Danko, bassist Hein Van de Geyn, and drummer John Engels. Released eleven months before his death, John Vinocur named it "a glorious moment in Chet Baker's twilight."[26]

In the winter of 1986, at a club in New York City, Baker met fashion photographer Bruce Weber.[27] Weber convinced him to do a photo shoot for what was originally going to be only a three-minute film.[28] When Baker started opening up to Weber, Weber convinced him to work on a longer film about his life.[29] Filming began in January 1987. The finished film, Let's Get Lost, is a highly acclaimed and stylized documentary that explores Baker's talent and charm, the glamour of his youth now withered into a derelict state, and his turbulent, sensational romantic and family life. It was released in September 1988, four months after his death that May. Two accompanying soundtrack albums, one compiling highlights from the height of his fame and one featuring new material that Baker recorded during the filming of the documentary, were released in 1989.

Death[edit]

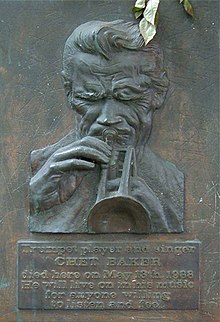

Early on May 13, 1988, Baker was found dead on the street below his room in Hotel Prins Hendrik, Amsterdam, with serious wounds to his head, apparently having fallen from the second-story window.[31] Heroin and cocaine were found in his room and in his body. No evidence of a struggle was found, and the death was ruled an accident.[32] According to another account, he inadvertently locked himself out of his room and fell while attempting to cross from the balcony of the vacant room adjacent to his own.[33] A plaque was placed outside the hotel in his memory.[34]

Baker is buried at the Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California,[35] next to his father.

Personal life[edit]

Chet Baker's personal life was tumultuous, partly owing to a decades-long drug addiction which began in the 1950s and a nomadic lifestyle caused by touring. In 1980, he referred to his life as "1/3 in a car, 1/3 sleeping, and 1/3 playing music."[22]

His first short-lived marriage was to Charlaine Souder in 1950.[6]: 43–44 In 1954, despite remaining married to Charlaine, he publicly dated French jazz club-goer Lili Cukier (later known as actress Liliane Rovère) for 2 years, introducing her to others as his wife.[36][6]: 102 A photo of the couple taken by William Claxton appears as part of a collage on the cover of Chet Baker Sings and Plays.

Baker's relationship with Lili ended when he informed her of his new marriage to Halema Alli.[6]: 128 He married the 20-year-old Halema, 7 years his junior, in May 1956, one month after they met.[6]: 132 The couple posed for a photograph by William Claxton, where Halema appears in a white dress and rests her head on Baker's knee. They had a son, Chesney Aftab Baker, to whom Baker dedicated his composition, "Chetty's Lullaby."[17] Baker was an irresponsible and distant father.[37]

In a scandal heavily scrutinized by Italian tabloids, Halema was sent to prison for smuggling jetrium from Germany to Italy for her husband, though she claimed that she was unaware that she was breaking the law. To his wife's humiliation, by the time of the trial, Baker had already started publicly dating Carol Jackson, a showgirl from Surrey. After being detained for six months,[8]: 86 Halema returned to Inglewood, and their marriage essentially ended, though they remained legally married for several years because tracking down Baker for divorce proceedings was too difficult.[6]: 169–171; 178

In 1962, Carol Jackson gave birth to a son, Dean. Two years later in 1964, Baker returned to the United States, and Halema was able to serve Baker divorce papers.[6]: 206 Baker married Carol Jackson in 1964, and they had two more children, Paul in 1965 and Melissa ("Missy") in 1966.[38][9][39][8]: x Despite his inconsistency in remaining in his family's life, and his infidelity, Carol and Chet never divorced.[9]

In 1970, Baker met jazz drummer Diane Vavra. The two started an on-again off-again relationship that lasted until the end of his life. Beginning in the 1980s, she acted as his steady companion while touring Europe.[8]: 117 She took care of his personal needs and assisted him with his career.[23] The Library of Congress holds the correspondence of Chet and Diane.[40] Chet dedicated his 1985 album Diane to Vavra, covering the familiar jazz standard "Diane." For a time, Vavra took refuge at a women's shelter due to Baker's behavior.[9]

In 1973, Baker began a relationship with Ruth Young, a jazz singer. She accompanied him on his 1975 tour in Europe, and he lived with her while stopping in New York.[8]: 116–117 They dated, with interruptions, for about a decade.[41][8]: 119 Together, they recorded two duets, "Autumn Leaves" and "Whatever Possessed Me," for the 1977 album The Incredible Chet Baker Plays and Sings.

Owing to his time in Italy, Baker was fluent in Italian.[22][42]

Baker enjoyed driving and sports cars.[43][8]: 132 In 1971, 1972, and 1975, Baker was arrested for drunk driving.[8]: 108

During the late 1960s and 1970s, Baker attempted to begin writing his memoirs. According to his wife Carol, he lost the draft while traveling on tour.[8]: 108 In 1997, Carol Baker published and wrote an introduction to his "lost memoirs," taped around 1978, under the title As Though I Had Wings.[1][44] What writing exists is scant and idiosyncratic, and focuses mainly on his time in the army and his drug use.

Compositions[edit]

Some of Baker's notable compositions include "Chetty's Lullaby", "Freeway", "Early Morning Mood", "Two a Day", "So che ti perderò" ("I Know I Will Lose You"), "Il mio domani" ("My Tomorrow"), "Motivo su raggio di luna" ("Contemplate on a Moonbeam"), "The Route", "Skidaddlin'", "New Morning Blues" (with Duke Jordan), "Blue Gilles", "Dessert", "Anticipated Blues", "Blues for a Reason",[45] "We Know It's Love", and "Looking Good Tonight".

Legacy[edit]

Baker was photographed by William Claxton for his book Young Chet: The Young Chet Baker. An Academy Award-nominated 1988 documentary about Baker, Let's Get Lost, portrays him as a cultural icon of the 1950s but juxtaposes this with his later image as a drug addict. The film, directed by fashion photographer Bruce Weber, was shot in black-and-white, and includes a series of interviews with friends, family (including his three children by third wife Carol Baker), musical associates, and female friends, interspersed with footage from Baker's earlier life, and interviews with Baker in his last years. In Chet Baker, His Life and Music, author Jeroen de Valk and others criticize the film for presenting Baker as a "washed-up" musician in his later years. The film was shot during the first half of 1987, prior to career highlights such as the Japanese concert, released on Chet Baker in Tokyo. It premiered four months after Baker's death.

Time after Time: The Chet Baker Project, written by playwright James O'Reilly, toured Canada in 2001.[46]

Jeroen de Valk has written a biography of Baker; Chet Baker: His Life and Music is the English translation.[47] Other biographies of him include James Gavin's Deep in a Dream—The Long Night of Chet Baker, and Matthew Ruddick's Funny Valentine. Baker's "lost memoirs" are available in the book As Though I Had Wings, which includes an introduction by Carol Baker.[1]

The 1960 film All the Fine Young Cannibals, starring Robert Wagner as a jazz trumpeter named Chad Bixby, was loosely inspired by Baker.

The 1999 film version of The Talented Mr. Ripley, Matt Damon plays a master of mimicry who imitates Baker's recording of "My Funny Valentine" from Chet Baker Sings.

Chet Baker is portrayed by Ethan Hawke in the 2015 film Born to Be Blue. It is a reimagining of Baker's career in the late 1960s, when he is famous for both his music and his addiction, and he takes part in a movie about his life to boost his career.[48] Steve Wall plays Baker in the 2018 film My Foolish Heart.

American singer/songwriter David Wilcox included the tender biographical portrait Chet Baker's Unsung Swan Song on his 1991 album Home Again.[49] Vocalist Luciana Souza recorded The Book of Chet in 2012 as a tribute. Brazilian jazz pianist Eliane Elias dedicated her 2013 album I Thought About You to Chet Baker.[50][51]

Australian musician Nick Murphy chose "Chet Faker" as his stage name as a tribute to Baker. Murphy said, "I listened to a lot of jazz and I was a big fan of ... the way he sang, when he moved into mainstream singing. He had this really fragile vocal style—this really, broken, close-up, and intimate style. The name is kind of just an ode to Chet Baker and the mood of music he used to play—something I would like to at least pay homage to in my own music."[52]

In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Baker at number 116 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[53]

Awards and honours[edit]

- Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame induction, 1987

- DownBeat magazine Jazz Hall of Fame, 1989

- Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame, 1991

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award for Chet Baker Sings (1956), inducted 2001[54]

- Chet Baker Day proclaimed by Oklahoma Governor Brad Henry and the Oklahoma House of Representatives, 2005

- Chet Baker Jazz Festival in his honor in Yale, Oklahoma, October 10, 2015

- Forlì Jazz Festival in honor of Chet Baker (30 years after his death), in Forlì, Italy, May 2–19, 2018

Discography[edit]

Filmography[edit]

- (1955) Hell's Horizon, by Tom Gries: actor

- (1959) Audace colpo dei soliti ignoti, by Nanni Loy: music

- (1960) Howlers in the Dock, by Lucio Fulci: actor

- (1963) Ore rubate ["stolen hours"], by Daniel Petrie: music

- (1963) Tromba Fredda, by Enzo Nasso: actor and music

- (1963) Le concerto de la peur, by José Bénazéraf: music

- (1964) L'enfer dans la peau, by José Bénazéraf: music

- (1964) Nudi per vivere, by Elio Petri, Giuliano Montaldo and Giulio Questi: music

- (1988) Let's Get Lost, by Bruce Weber: music

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Ruhlmann, William. "Chet Baker". AllMusic. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ Carr, Roy (December 2, 2004). "A century of jazz". London : Hamlyn – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gelly, Dave (2000). Icons of Jazz: A History in Photographs, 1900–2000 (North American ed.). San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. ISBN 1-57145-268-0.

- ^ Leland, John (October 5, 2004), Hip: The History, HarperCollins, pp. 265–, ISBN 978-0-06-052817-1, retrieved November 13, 2015

- ^ a b c d Gioia, Ted (1998). West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945-1960. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520217294.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gavin, James (2011). Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781569767573.

- ^ "Chet Baker | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Valk, Jeroen de (2000). Chet Baker: His Life and Music. Berkeley Hills Books. ISBN 9789463381987.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weber, Bruce (September 15, 1988). Let's Get Lost (Documentary film). Zeitgeist Films.

- ^ a b "Chet Baker". AllMusic. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ McKeever, Stuart A. (June 19, 2014). Becoming Joey Fizz. Author House. pp. 17–. ISBN 9781496915214. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Cahill, Greg. "Chet Baker". North Bay Bohemian. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Robert (1986). Jazz West Coast : the Los Angeles jazz scene of the 1950s. Quartet Books. p. 72. ISBN 9780704326033.

- ^ Davis Inman (January 16, 2012). "Chet Baker, 'My Funny Valentine'". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ "Review spotlight on... Jazz Albums". Billboard. November 10, 1956. p. 86. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ a b Myers, Mark (February 4, 2020). "Chet Baker + Caterina Valente". JazzWax. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c Myers, Mark (July 21, 2017). "Chet Baker: La Voce". JazzWax. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Chet Baker - 1959 Milano Sessions - Promo Sound, CD 4312 ADD

- ^ Myers, Mark (April 16, 2012). "Chet Baker: New York, 1964". JazzWax. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "A Taste of Tequila Review". AllMusic. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (June 12, 2002). "'Cool' jazz's tortured king / Drugs, abuse marked trumpeter's career". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b c rendarte piaz (1980). Chet Baker interview about drug and jazz1980 (in Italian). YouTube. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Chet Baker resided and played almost exclusively in Europe". jazzbluesnews.com. December 22, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Enos, Morgan (April 22, 2022). "Chet Baker Trio: Live in Paris: The Radio France Recordings 1983-1985 (Elemental)". JazzTimes. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Wulff, Ingo (1993). Chet Baker in Europe: 1975-1988 (in German and English). Nieswand Verlag. ISBN 9783926048578.

- ^ Vinocur, John (February 22, 2008). "A glorious moment in Chet Baker's twilight". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Adams, James (September 9, 2006). "Through a Legend, Darkly". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Kreigmann, Jame (December 1988). "Requiem for a Horn Player". Esquire. p. 231.

- ^ James, Nick (June 2008). "Return Of The Cool". Sight & Sound. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Zhuk, Roman. "News - Chet Baker (memorial plaque)". Roman-Zhuk.com. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (May 14, 1988). "Chet Baker, Jazz Trumpeter, Dies at 59 in a Fall". The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "Chet Baker: het roerige leven van een jazzlegende". USA365 (in Dutch). May 18, 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Tom Schnabel (January 17, 2012). "How Chet Baker Really Died". KCRW.com. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ thelastgps (August 21, 2012). "Chet Baker - Amsterdam - May 13, 1988". The Last GPS. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Notable Lives | Inglewood Park Cemetery". January 23, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Merle, Sylvain (April 11, 2019). "Liliane Rovère, actrice dans "Dix Pour Cent" : "Je suis une rescapée"". Le Parisien (in French). Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ St. Clair, Jeffrey (November 25, 2011). "Scenes From the Life of Chet Baker". CounterPunch. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ "Bruce Guthrie: Remembering Chet Baker article @ All About Jazz". All About Jazz. April 23, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Murray, Ruby (January 1, 2012). "Chet Baker historical profile | Dumbo Feather Magazine". Dumbo Feather. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Miller, Cait (May 26, 2020). "Chet Baker, Heart and Soul". Library of Congress Blogs. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ Gladstone, Michael P. (July 14, 2005). "Ruth Young: This Is Always review". AllAboutJazz. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Chet in italiano.mov, archived from the original on October 31, 2021, retrieved March 15, 2021

- ^ "Carol Baker, Chet Baker's widow". Jerry Jazz Musician. June 22, 1998. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Bouchard, Fred (April 19, 2019). "As Though I Had Wings: The Lost Memoir by Chet Baker". JazzTimes. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Chet Baker Quintet* Featuring Warne Marsh - Blues For A Reason". Discogs. November 13, 1985. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Crew, Robert (April 6, 2001). "Time After Time: The Chet Baker Project". Variety. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ "Jeroen de Valk: tekst & muziek". Jeroendevalk.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (February 4, 2015). "Berlin: Ethan Hawke Brings Jazz Pic 'Born to Be Blue' to Fest". Variety. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ Iyengar, Vik. "David Wilcox -- Home Again". AllMusic.com. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Collar, Matt. "Eliane Elias -- I Thought About You". AllMusic.com. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ Bailey, C. Michael (May 23, 2013). "Eliane Elias: I Thought About You: A Tribute to Chet Baker". All About Jazz. allaboutjazz.com. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ "Discovery: Chet Faker". Interview Magazine. March 16, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "The 200 Greatest Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. January 1, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "GRAMMY Hall Of Fame". Grammy.com. October 18, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Baker, Chet; Carol Baker. As Though I Had Wings: The Lost Memoir. St Martins Press, 1997.

- De Valk, Jeroen. Chet Baker: His Life and Music. Berkeley Hills Books, 2000. ISBN 18-931-6313-X. Updated and expanded edition: Chet Baker: His Life and Music. Uitgeverij Aspekt, 2017. ISBN 9789461539786.

- Gavin, James. Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

- Ruddick, Matthew. Funny Valentine: The Story of Chet Baker. Melrose Books, 2012.

External links[edit]

Media related to Chet Baker at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chet Baker at Wikimedia Commons- Chet Baker at AllMusic

- Chet Baker at IMDb

- Chet Baker at Find a Grave

- "Baker, Chet", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

- Chet Baker Materials from the papers of Diane Vavra, 1970-1989 at the Library of Congress

- Chet Baker Live Recordings from Circle Records Germany

- Chet Baker

- 1929 births

- 1988 deaths

- Jazz musicians from Oklahoma

- People from Milpitas, California

- People from Payne County, Oklahoma

- 20th-century American singers

- 20th-century trumpeters

- Accidental deaths from falls

- Accidental deaths in the Netherlands

- American jazz singers

- American jazz trumpeters

- American male trumpeters

- American people of Norwegian descent

- Burials at Inglewood Park Cemetery

- Columbia Records artists

- Cool jazz musicians

- Cool jazz singers

- Cool jazz trumpeters

- Drug-related deaths in the Netherlands

- EmArcy Records artists

- Enja Records artists

- Galaxy Records artists

- Hot Club Records artists

- Prestige Records artists

- Riverside Records artists

- SteepleChase Records artists

- Timeless Records artists

- Transatlantic Records artists

- Verve Records artists

- United States Army Band musicians

- American male jazz musicians

- CTI Records artists

- Sonet Records artists

- 20th-century American male singers

- Jazz musicians from California