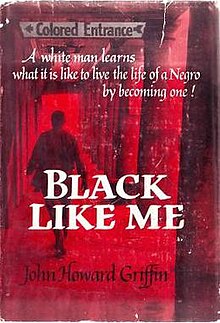

Black Like Me

First edition | |

| Author | John Howard Griffin |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin |

Publication date | 1961 |

| 305.896073 | |

| LC Class | E185.61 .G8 |

Black Like Me, first published in 1961, is a nonfiction book by journalist John Howard Griffin recounting his journey in the Deep South of the United States, at a time when African-Americans lived under racial segregation. Griffin was a native of Mansfield, Texas, who had his skin temporarily darkened to pass as a black man. He traveled for six weeks throughout the racially segregated states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, and Georgia to explore life from the other side of the color line. Sepia Magazine financed the project in exchange for the right to print the account first as a series of articles.

Griffin kept a journal of his experiences; the 188-page diary was the genesis of the book. When he started his project in 1959, race relations in America were particularly strained. The title of the book is taken from the last line of the Langston Hughes poem "Dream Variations".

In 1964, a film version of Black Like Me, starring James Whitmore, was produced.[1] A generation later, Robert Bonazzi published a biographical book about Griffin, these events, and his life: Man in the Mirror: John Howard Griffin and the Story of Black Like Me (1997).

Account of the trip[edit]

In late 1959, John Howard Griffin went to a friend's house in New Orleans, Louisiana. Once there, under the care of a dermatologist, Griffin underwent a regimen of large oral doses of the anti-vitiligo drug methoxsalen, and spent up to 15 hours daily under an ultraviolet lamp for about a week. He was given regular blood tests to ensure that he was not suffering liver damage. The darkening of his skin was not perfect, so he touched it up with stain. He shaved his head bald to hide his straight brown hair. Satisfied that he could pass as an African-American, Griffin began a six-week journey in the South. Don Rutledge traveled with him, documenting the experience with photos.[2]

During his trip, Griffin abided by the rule that he would not change his name or alter his identity; if asked who he was or what he was doing, he would tell the truth.[3] In the beginning, he decided to talk as little as possible[4] to ease his transition into the social milieu of southern U.S. blacks. He became accustomed everywhere to the "hate stare" received from whites.

After he disguised himself, many people who knew Griffin as a white man did not recognize him. Sterling Williams, a black shoeshine man in the French Quarter whom Griffin regarded as a casual friend, did not recognize him. He first hinted that he wore the same unusual shoes as somebody else,[5] but Sterling still did not recognize him until Griffin told him. Because Griffin wanted assistance in entering into the black community, he decided to tell Williams about his identity and project.

In New Orleans, a black counterman at a small restaurant chatted with Griffin about the difficulties of finding a place to go to the bathroom, as facilities were segregated and blacks were prohibited from many. He turned a question about a Catholic church into a joke about "spending much of your time praying for a place to piss".

On a bus trip, Griffin began to give his seat to a white woman, but disapproving looks from black passengers stopped him. He thought he had a momentary breakthrough with the woman, but she insulted him and began talking with other white passengers about how impudent the blacks were becoming.

Griffin decided to end his journey in late November in Montgomery, Alabama. He spent three days secluded from sunlight in a hotel room and stopped taking his skin-darkening medication. When his skin had regained its natural color, he quietly slipped into the white part of Montgomery, and was jarred by how warmly the people there now treated him.[6]

Reaction[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2017) |

After his book was published, Griffin received many letters of support. He said they helped him understand the experience. Griffin received very few hostile letters.[7]

Griffin became a national celebrity for a time. In a 1975 essay included in later editions of the book, he recounted encountering hostility and threats to him and his family in his hometown of Mansfield, Texas. He moved to Mexico for a number of years for safety.[8][9]

In 1964, while stopped with a flat tire in Mississippi, Griffin was assaulted by a group of white men and beaten with chains, an assault attributed to the book. It took five months to recover from the injuries.[10]

Precedent[edit]

Journalist Ray Sprigle of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had undertaken a similar project more than a decade earlier.

Publication history[edit]

Sepia Magazine financed the project in exchange for the right to print the account first as a series of articles, which it did under the title Journey into Shame.

United States[edit]

- John Howard Griffin (1961). Black Like Me. Houghton Mifflin. LCCN 61005368.

- John Howard Griffin (1962). Black Like Me. Signet Books. ISBN 0-451-09703-3.

- John Howard Griffin (1977). Black Like Me. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-25102-8.

- 2nd Edition, with an epilogue by the author, written three years before his death in 1980.

- John Howard Griffin (1996). Black Like Me: 35th Anniversary Edition. Signet. ISBN 0-451-19203-6.

- With an epilogue by the author and a new afterword by Robert Bonazzi. Library-bound printing is ISBN 0-88103-599-8

- John Howard Griffin (1999). Black Like Me. Buccaneer Books. ISBN 1-56849-730-X.

- John Howard Griffin (2003). Black Like Me. New American Library Trade. ISBN 0-451-20864-1.

- John Howard Griffin (2004). Black like Me: The Definitive Griffin Estate Edition, Corrected from Original Manuscripts. Wings Press. ISBN 0-930324-72-2.

- New edition. With a foreword by Studs Terkel, historic photographs by Don Rutledge, and an afterword by Robert Bonazzi. Library-bound printing is ISBN 0-930324-73-0

- John Howard Griffin (2010). Black Like Me (50th Anniversary Edition). Signet. ISBN 978-0451234216.

UK[edit]

- John Howard Griffin (1962). Black Like Me. Collins.

- John Howard Griffin (1962). Black Like Me. The Catholic Book Club.

- John Howard Griffin (1962). Black Like Me. Grafton Books. ISBN 0-586-02482-4. (repeatedly reprinted under same ISBN)

- John Howard Griffin (1964). Black Like Me. Panther. ISBN 0-586-02824-2.

- John Howard Griffin (2009). Black Like Me. Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-63857-0.

Cultural references[edit]

The title of the song "Black Like Me" (2020) by Mickey Guyton was inspired by the book.[11]

Episode 15 of season 4 of the television series Boy Meets World was titled "Chick Like Me". In it, Mr. Feeny discusses Black Like Me, which gives Shawn the idea for him and Cory to dress likes girls to see if they get treated differently as a topic for Cory's column in the school newspaper.

The television drama film To Be Fat like Me (2007) was loosely inspired by the book. It stars Kaley Cuoco as a thin woman who makes herself appear overweight by wearing a fat suit, and films her experiences for a documentary titled Fat Like Me.

See also[edit]

- Civil Rights Movement

- Grace Halsell, a white investigative reporter who lived for a time as a black woman and wrote the book Soul Sister (1969) about her experience.

- Lowest of the Low (German: Ganz unten), a similar book about Turks in Germany written by Günter Wallraff

- The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for African-American travelers published annually 1936–1966

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

Citations[edit]

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (May 21, 1964). "Black Like Me (1964) James Whitmore Stars in Book's Adaptation". The New York Times.

- ^ Stanley Leary. "Black Like Me". Archived from the original on June 6, 2015.

- ^ "I decided not to change my name or identity...If asked who I was or what I was doing, I would answer truthfully..." (p. 4) Black Like Me, Signet & New American Library, a division of Penguin Group publishers.

- ^ "I had made it a rule to talk as little as possible at first." (p. 23)

- ^ "He looked up without a hint of recognition...He had shined them many times and I felt he should certainly recognize them." (p. 26)

- ^ Robert Bonazzi (1997), Man in the Mirror, p. 106

- ^ "There were six thousand letters to date and only nine of them abusive." (p. 184)

- ^ Connolly, Kevin (October 25, 2009). "Exposing the colour of prejudice". BBC News.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (March 17, 2007), "John Howard Griffin Took Race All the Way to the Finish", The Washington Post

- ^ Manzoor, Sarfraz (October 27, 2011). "Rereading: Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ Jonathan Bernstein (June 5, 2020). "Mickey Guyton on Country Music's Response to George Floyd's Death". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

General and cited references[edit]

- Robert Bonazzi (1997). Man in the Mirror. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60940-135-1.