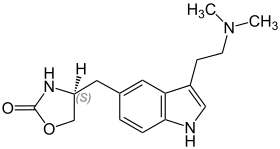

Antimigraine drug

| Antimigraine drug | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Zolmitriptan, a common antimigraine medication | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Migraine therapy and prevention |

| ATC code | N02C |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Antimigraine drugs are medications intended to reduce the effects or intensity of migraine headache. They include drugs for the treatment of acute migraine symptoms as well as drugs for the prevention of migraine attacks.[1]

Treatment of acute symptoms[edit]

Examples of specific antimigraine drug classes include triptans (first line option), ergot alkaloids, ditans and gepants. Migraines can also be treated with unspecific analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen. Opioids are not recommended for treatment of migraines.

Triptans[edit]

The triptan drug class includes 1st generation sumatriptan (which has poor bioavailability), and second generation zolmitriptan.[2] Due to their safety, efficacy and selectivity, triptans are considered first line agents for abortion of migraines.[2] These medications are selective 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists with some activity at 5-HT1F. They produce an antimigraine effect by vasoconstriction of the vessels in the brain, as well as inhibiting trigeminal CGRP release and pain transmission.[2] They are normally well tolerated but the vasoconstrictor effects can lead to problematic side effects such as nausea, dizziness and chest discomfort, and therefore require caution in patients with cardiovascular disease.[2] There is also an increased risk of gastrointestinal adverse events.[3] Triptans use is limited to less than ten times per month in order to reduce Medication Overuse Headache (MOH).[2]

Ergots alkaloids[edit]

Ergot alkaloids include ergotamine and dihydroergotamine. This medication class targets the GCRP receptor pathway due to their likeness to serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline. They show activity at serotonin 5-HT1-2, dopamine D2-like and alpha1/alpha2-adrenoreceptors.[4] Their lack of selectivity leads to more adverse effects, making them second line compared to triptans.[4] However, they have been shown to prevent recurrence better than triptans.[5] Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, paresthesia, and ergotism.[2] Their use is limited to less than ten times per month in order to reduce medication overuse headaches (MOH's). The oral dosage administrative form is considered less effective than nasal or parenteral forms and has been discontinued in Canada.[5] Ergotamine is contraindicated during pregnancy.[6]

Ditans[edit]

Ditans (eg. lasmiditan) are a new group of anti migraine drugs which were developed due some of the concerns with the 1st line triptans (eg. adverse effects, concern with use in cardiovascular disease, use of less than 10x per month to reduce MOH). Ditans are 5-HT1F receptors agonists.[7] Lasmiditan has been suggested to have less pain relief when compared to the triptans at the 2 hour mark post taking the medication. Lasmitan was shown to have higher adverse events (dizziness, fatigue and nausea) than the triptans or another novel medication class, GCRP antagonists.[7] However, they could be an option for patients with cardiovascular risks due to their lack of vasoconstriction .[7] Due to risk of dizziness, those who take lasmiditan should avoid driving 8 hours after taking.[3]

Gepants[edit]

Gepants (eg. rimegepant, ubrogepant, and atogepant) are also a new group of anti migraine drugs, along with ditans. They are calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists.[7] Gepants have been suggested to have less pain relief at 2 hours compared to triptans. Similar to ditans, they offer another therapy option that does not include vasoconstriction, thus may be suitable for those with cardiovascular risk factors.[7] They are well tolerated with fewer adverse effects compared to triptans .[7]

NSAIDS[edit]

NSAIDS are a nonspecific medication used for abortion of migraines due to their analgesic properties. They can be used for mild to moderate migraines, but are less effective against severe migraines.[8] Similar to the triptans and ergots alkaloids, their use should be limited to less than 10x per month to reduce MOH. Acetaminophen is an analgesic that can also be used, but NSAIDS should be tried first due to their anti-inflammatory properties. However, acetaminophen would be considered first line in pregnant patients.[6] Combination therapy of an NSAID with a triptan can be used when either medication is insufficient alone for migraine relief or recurrence .[5] Long term NSAID use has risks including nephrotoxicity and cardiotoxicity, and long term acetaminophen use is associated with hepatoxicity.[3] If warranted, an antiemetic can be used in combination with an NSAID.[8]

Opioids[edit]

Opioids are not recommended for treatment of acute migraines due to their significant side effect profile, including twice the risk of medication overuse headache when compared to NSAIDS, acetaminophen or triptans.[3] In addition, their strength of efficacy has showed to be low or insufficient for pain relief of migraines.[3] Importantly, there is also risk of addiction and opioid use disorder.[3]

Prevention[edit]

For patients who require preventive therapy with symptoms such as more than 4 migraines per month or migraines lasting longer than 12 hours, first-line drugs for the prevention of migraine attacks include beta blockers, antidepressants, and anti convulsants.

Beta Blockers[edit]

Beta blockers have been deemed effective options for the prevention of migraines. In particular, metoprolol, timolol and propranolol have the most strength of efficacy.[9] The timeframe to effectiveness in generally within 3 months.[9] Patients with cardiovascular risk factors should avoid the use of beta blockers for migraine prevention.[9]

Antidepressants[edit]

Antidepressants are suggested to be both efficacious and tolerable in the treatment of migraine prevention for both migraine frequency and migraine index.[10] The exact mechanism of action is unknown but seems to be related to serotonin's impact on migraine.[10] In particular, amitryptyline (a tricyclic antidepressant) has the most evidence to suggest its efficacy.[10] Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors as well as serotonin and norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors are likely effective as well, but more studies are required in order to provide more evidence.[10] Adverse events of antidepressants can include fatigue, nausea, drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, GI upset and weakness.[10] Sedation is also common.[9]

Anticonvulsants[edit]

Both sodium valproate and divalproex sodium have been established as efficacious for migraine prophylaxis.[11] They are well tolerated short term, but should be monitored during long term therapy because of risks of pancreatitis, liver failure and teratogenicity.[12] Valproate should not be used in females of childbearing age because studies suggest that children exposed to valproate in the prenatal period are associated with having lower IQ scores.[9] Topiramate is another anticonvulsant with therapeutic efficacy in migraine prophylaxis.[13] It is a safe medication but should be used in caution in females of childbearing ages because it is suggested to cause birth defects.[13]

Calcitonin gene receptor peptide (CGRP) antagonists[edit]

CGRP antagonists can be used for both acute migraine treatment as well as prophylactically.[14] CGRP is a neuropeptide which is thought to induce migraines via vasodilation of cranial arteries.[14] CGRP can also release inflammatory agents and cause nervous system sensitization.[14] It is theorized that by antagonizing the CGRP receptor of the trigeminal ganglia, lowered CGRP is released and less migraine occurs.[14] Erenumab is a highly selective human monoclonal antibody which is a promising new development in migraine treatment.[14] It has low risk of hepatoxicity like gepants can have, due to being mostly eliminated via proteolysis.[15]

Melatonin[edit]

There have been some studies suggesting the benefit of using melatonin for prophylaxis of migraine, however, there is a lack of strength of evidence due to a low number of studies as well as conflicting results.[16] Melatonin has a good safety profile but there have been rare instances of serious side effects.[16] More studies are needed in order to suggest the therapeutic use of melatonin for prophylaxis of migraine.[16]

Prophylaxis in pediatric patients[edit]

There is not a strong degree of evidence for the use of anti migraine drugs prophylactically in children and adolescence.[17] It is highly important to consider risk vs benefit when considering their use in the paediatric population.[17]

References[edit]

- ^ Mutschler E (2013). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (10 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 232–5. ISBN 978-3-8047-2898-1.

- ^ a b c d e f González-Hernández A, Marichal-Cancino BA, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Villalón CM (January 2018). "Side effects associated with current and prospective antimigraine pharmacotherapies". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 14 (1): 25–41. doi:10.1080/17425255.2018.1416097. PMID 29226741. S2CID 35889312.

- ^ a b c d e f VanderPluym JH, Halker Singh RB, Urtecho M, Morrow AS, Nayfeh T, Torres Roldan VD, et al. (June 2021). "Acute Treatments for Episodic Migraine in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA. 325 (23): 2357–2369. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7939. PMC 8207243. PMID 34128998.

- ^ a b Tfelt-Hansen PC (September 2013). "Triptans and ergot alkaloids in the acute treatment of migraine: similarities and differences". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 13 (9): 961–963. doi:10.1586/14737175.2013.832851. PMID 23980649. S2CID 19114584.

- ^ a b c Osman N, Worthington I, Lagman-Bartolome A. "General Appendices: Headache in Adults: Self-care Therapy for Common Conditions". Compendium of Therapeutics for Minor Ailments (2nd (CTMA 2) ed.). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Pharmacists Association. ISBN 978-1-894402-96-5.

- ^ a b Lee MJ, Guinn D, Hickenbottom S (April 25, 2022). "Headache during pregnancy and postpartum". UpToDate.

- ^ a b c d e f Yang CP, Liang CS, Chang CM, Yang CC, Shih PH, Yau YC, et al. (October 2021). "Comparison of New Pharmacologic Agents With Triptans for Treatment of Migraine: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Network Open. 4 (10): e2128544. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28544. PMC 8506232. PMID 34633423.

- ^ a b Schwedt TJ, Garza MI (April 25, 2022). "Acute treatment of migraine in adults". UpToDate.

- ^ a b c d e Schwedt TJ, Garza MI (March 11, 2022). "Preventative treatment of episodic migraine in adults". Up to Date. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Xu XM, Yang C, Liu Y, Dong MX, Zou DZ, Wei YD (August 2017). "Efficacy and feasibility of antidepressants for the prevention of migraine in adults: a meta-analysis". European Journal of Neurology. 24 (8): 1022–1031. doi:10.1111/ene.13320. PMID 28557171. S2CID 4572477.

- ^ Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E (April 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 78 (17): 1337–1345. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20. PMC 3335452. PMID 22529202.

- ^ Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E (April 2012). "Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 78 (17): 1337–1345. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20. PMC 3335452. PMID 22529202.

- ^ a b Linde M, Mulleners WM, Chronicle EP, McCrory DC, et al. (Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group) (June 2013). "Topiramate for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (6): CD010610. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010610. PMC 7388931. PMID 23797676.

- ^ a b c d e Urits I, Jones MR, Gress K, Charipova K, Fiocchi J, Kaye AD, Viswanath O (March 2019). "CGRP Antagonists for the Treatment of Chronic Migraines: a Comprehensive Review". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 23 (5): 29. doi:10.1007/s11916-019-0768-y. PMID 30874961. S2CID 78092916.

- ^ Szkutnik-Fiedler D (December 2020). "Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Drug-Drug Interactions of New Anti-Migraine Drugs-Lasmiditan, Gepants, and Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies". Pharmaceutics. 12 (12): 1180. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics12121180. PMC 7761673. PMID 33287305.

- ^ a b c Long R, Zhu Y, Zhou S (January 2019). "Therapeutic role of melatonin in migraine prophylaxis: A systematic review". Medicine. 98 (3): e14099. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000014099. PMC 6370052. PMID 30653130.

- ^ a b Locher C, Kossowsky J, Koechlin H, Lam TL, Barthel J, Berde CB, et al. (April 2020). "Efficacy, Safety, and Acceptability of Pharmacologic Treatments for Pediatric Migraine Prophylaxis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". JAMA Pediatrics. 174 (4): 341–349. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856. PMC 7042942. PMID 32040139.