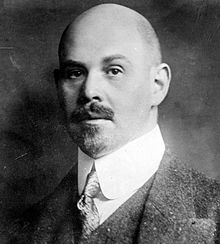

Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Foreign Minister of Germany | |

| In office 1 February – 24 June 1922 | |

| President | Friedrich Ebert |

| Chancellor | Joseph Wirth |

| Preceded by | Joseph Wirth (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Wirth (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 September 1867 Berlin, North German Confederation |

| Died | 24 June 1922 (aged 54) Berlin, Weimar Republic |

| Political party | German Democratic Party |

| Relations | Emil Rathenau (father) |

| Profession | Industrialist, politician, writer |

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Walther Rathenau (German: [ˈvaltɐ ˈʁaːtənaʊ]; 29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and politician who served as foreign minister of Germany from February to June 1922.

Rathenau was one of Germany's leading industrialists in the late German Empire. During World War I, he played a key role in the organisation of the German war economy and headed the War Raw Materials Department from August 1914 to March 1915.

After the war, Rathenau was an influential figure in the politics of the Weimar Republic. In 1921 he was appointed minister of reconstruction and a year later became foreign minister. Rathenau negotiated the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo, which normalised relations and strengthened economic ties between Germany and Soviet Russia. The agreement, along with Rathenau's insistence that Germany fulfil its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles, led right-wing nationalist groups (including a nascent Nazi Party) to brand him part of a Jewish-communist conspiracy.[1]

Two months after the signing of the treaty, Rathenau was assassinated by members of the ultra-nationalist Organisation Consul in Berlin. His death was followed by national mourning as well as widespread demonstrations against counter-revolutionary terrorism, which briefly strengthened the Weimar Republic. Rathenau came to be viewed as a democratic martyr during the Weimar era.[2] After the Nazis came to power in 1933, all commemorations of Rathenau were banned.

Early life[edit]

Rathenau was born in Berlin to Emil Rathenau, a prominent Jewish businessman and founder of the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), a producer of electricity and electrical equipment, and Mathilde Nachmann.[3]

Education and business experience[edit]

Rathenau studied physics, chemistry and philosophy in Berlin and Strasbourg, and received a doctorate in physics in 1889 after studying under August Kundt.[4]

Rathenau worked as a technical engineer in a Swiss aluminium factory and then as a manager in a small electro-chemical firm in Bitterfeld, where he conducted experiments in electrolysis. He returned to Berlin and joined the AEG board in 1899,[3] becoming a leading industrialist in the late German Empire and early Weimar Republic. He set up power stations in Manchester, Buenos Aires and Baku. AEG acquired ownership of a streetcar company in Madrid, and in East Africa he purchased a British firm. In total he was involved with 84 companies worldwide.[5] AEG was particularly praised for vertical integration methods and a strong emphasis on supply chain management. Rathenau developed an expertise in business restructuring and turning companies around. His strong organizational abilities made his company very successful. He made substantial profits from commercial lending on a wide industrial scale, which he then reinvested in capital and assets.

Visits to Germany's African colonies[edit]

During the same period, Rathenau was becoming interested in politics. He became close friends with the businessman Bernhard Dernburg, who was appointed Germany's first colonial secretary in May 1907. Dernburg introduced Rathenau to Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, who agreed that at his own expense Rathenau could accompany Dernburg on official visits to the colonies of German East Africa in 1907 and German Southwest Africa in 1908. Soon after returning from East Africa, Rathenau submitted a report to the German government which was influential in developing official policy towards the colony. Like Dernburg, Rathenau believed that African workers were the most valuable resource in the colony and that it was essential to care for their well-being. Rathenau also argued that the colonial justice system must treat Africans fairly.[6][7]

During his time in German South West Africa, Rathenau condemned the treatment of the Herero people, referring to the Herero and Namaqua genocide as "the greatest atrocity that has ever been brought about by German military policy".[8] He condemned the "system of deportation and concentration camps" and described the "present position of the native" as having the "outward appearance of slavery".[9]

Thoughts on German Jews[edit]

Rathenau's main personal characteristics were courage, vision, imagination, tenacity and creativity. Along with seeing pleasure from profit's ability to elevate society as one of the joys of work, he also wrote about personal and social responsibility to the community and insisted that technology come to the aid of manual labourers. According to one biographer, Rathenau had a sense of inferiority in society that was due to his Jewishness, writing that over time Rathenau realised "that he had come into the world as a second-class citizen and that no amount of ability and merit could ever free him from the condition".[10]

His German Jewish heritage and his accumulated wealth were both factors in establishing his deeply divisive reputation in German politics at a time of increasingly widespread antisemitism in Germany.[11] In a 1918 book, he summed up his thoughts on growing up Jewish in Germany, writing that his patriotism and loyalty to his country were no different than that of any fellow German regardless of religion or ethnicity:[12]

I am a German of Jewish origin. My people are the German people, my homeland is Germany, my faith is German faith, which stands above denominations.

At the time, there was a widespread belief in Germany that Jews could never put their country first. The idea that the Jews were "our misfortune", as the German nationalist historian Heinrich Treitschke wrote, led to the proliferation from the 1880s of antisemitic parties.[a] There were no Jewish officers in the Prussian Army – the ruling class in the Imperial Officer Corps was both outspokenly and latently antisemitic and eventually supported the Nazis' antisemitic policies.[13]

Rathenau was a strong proponent of full and radical assimilation of German Jews into German society. In his 1897 article Höre, Israel! ("Hear, O Israel!"), he wrote:[14]

Strange sight! In the midst of German life an isolated, strange human tribe, resplendently and conspicuously adorned, hot-blooded and animated in its behaviour. An Asian horde on the soil of the March of Brandenburg. The forced cheerfulness of these people does not betray the amount of old, unquenched hatred that rests on their shoulders. Little do they know that only an age that keeps all natural forces in check is able to protect them from what their fathers would have suffered. In close association with each other, strictly closed off from the outside – thus they live in a semi-voluntary, invisible ghetto, not a living member of the people but a foreign organism in its body. ... What, then, must happen? An event without historical precedent: the conscious self-education of a race to assimilate to outside demands. ... Assimilation in the sense that tribal qualities – regardless of whether they are good or bad – that are demonstrably hateful to fellow Germans are cast off and replaced by more suitable ones. ... The goal of the processes should not be imitation Germans, but Jews who are German by nature and education.

In government[edit]

War Raw Materials Department[edit]

Rathenau played a key role in convincing the War Ministry to set up the War Raw Materials Department (Kriegsrohstoffabteilung, KRA), of which he was put in charge in August 1914 and where he established its fundamental policies and procedures. The KRA focused on raw materials threatened by the British blockade, as well as supplies from occupied Belgium and France. It set prices, regulated the distribution to vital war industries and began the development of substitute raw materials.[15]

He left the KRA in March 1915 and became president of AEG upon his father's death in June of that year.[3]

Postwar statesman[edit]

Rathenau was a moderate liberal in politics. After World War I, he joined the German Democratic Party (DDP) and moved to the left in the face of postwar chaos. Passionate about social equality, he rejected state ownership of industry and instead advocated greater worker participation in the management of companies.[16] His ideas were influential in postwar governments, although in 1919 when his name was mentioned in the Weimar National Assembly as a candidate for president of Germany, there was a burst of laughter among the other members.[17] Referring to the extreme right-wing organizations that arose within months of the communist-inspired Spartacist uprising in January 1919, he said in the Reichstag that they were, "the product of a state in which for centuries no one has ruled who was not a member of, or a convert to, military feudalism".[citation needed]

In 1920, he worked on the Socialisation Commission, a group of experts set up by the Council of the People's Deputies in November 1918 to examine ways of socialising parts of the German economy, and took part in the Spa Conference, at which German disarmament and reparations were discussed. Because of his international reputation and negotiating skills, he became minister of reconstruction in Chancellor Joseph Wirth's cabinet in May 1921. He supported Wirth's "fulfilment policy", which attempted to show that Germany was unable to meet the Entente's reparations demands by making a good faith effort to fulfil them. In October he concluded the Wiesbaden Agreement with France on private-sector German deliveries of goods to French war victims. Rathenau resigned as minister at the end of October when the DDP withdrew from the governing coalition, but he continued to work for the government in London and at the Cannes Conference on reparations.[3]

Foreign minister[edit]

In 1922, Rathenau became foreign minister in Wirth's second cabinet. His insistence that Germany should fulfil its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles but work for a revision of its terms infuriated extreme German nationalists.[18] He also angered them by negotiating the Treaty of Rapallo with the Soviet Union, which was signed on 16 April 1922 on the sidelines of the Conference of Genoa. The Rapallo Treaty, which normalised relations between Germany and the USSR, allowed Germany to return to the international diplomatic stage but isolated it from the Western powers.[19]

The leaders of the still obscure Nazi Party and other extremist groups claimed that he was part of a "Jewish-communist conspiracy", despite the fact that he was a liberal German nationalist who had bolstered the country's war effort.[1] The British politician Robert Boothby wrote of him, "He was something that only a German Jew could simultaneously be: a prophet, a philosopher, a mystic, a writer, a statesman, an industrial magnate of the highest and greatest order, and the pioneer of what has become known as 'industrial rationalisation'."[20]

Assassination and aftermath[edit]

On 24 June 1922, two months after the signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, Rathenau was assassinated. He was being chauffeured from his house in Berlin-Grunewald to the Foreign Office in the Wilhelmstraße when his car was passed by another with Ernst Werner Techow behind the wheel and Erwin Kern and Hermann Fischer in the back seat. Kern opened fire with a submachine gun at close range, killing Rathenau almost instantly, while Fischer threw a hand grenade into the car before Techow quickly drove them away.[21] Also involved in the plot were Techow's younger brother Hans Gerd Techow, future writer Ernst von Salomon, and Willi Günther (aided and abetted by seven others, some of them schoolboys). All conspirators were members of the ultra-nationalist secret Organisation Consul.[22] A memorial stone in the Königsallee in Grunewald marks the scene of the crime.

Historian Martin Sabrow points to Hermann Ehrhardt, the leader of the Organisation Consul, as the one who ordered the murders. Ehrhardt and his men believed that Rathenau's death would bring down the government and prompt the Left to act against the Weimar Republic, thereby provoking civil war in which the Organisation Consul would be called on for help by the Reichswehr. After an anticipated victory Ehrhardt hoped to establish an authoritarian regime or a military dictatorship. He carefully saw to it that no connections between him and the assassins could be detected. Although Fischer and Kern contacted the Berlin chapter of the Organisation Consul to use its resources, they mainly acted on their own in planning and carrying out the assassination.[23] The historian Michael Kellogg argued that Vasily Biskupsky, Erich Ludendorff and his advisor Max Bauer, all members of the Aufbau Vereinigung, a group of tsarist exiles and early Nazis, colluded in the assassination of Rathenau, although the degree of their participation was not entirely clear.[24]

Millions of Germans gathered on the streets to express their grief and demonstrate against counter-revolutionary terrorism. When the news of Rathenau's death became known in the Reichstag, the session turned into turmoil. DNVP politician Karl Helfferich in particular became the target of scorn because he had recently made a vitriolic attack upon Rathenau.[25] During the official memorial ceremony the next day, Chancellor Joseph Wirth from the Centre Party made a speech which soon became famous. While pointing to the right side of the parliamentary floor, he said, "There is the enemy – and there is no doubt about it: The enemy is on the right!"[26]

The crime itself was soon cleared up. Willi Günther had bragged about his participation in public. After his arrest on 26 June, he confessed to the crime without holding anything back. Hans Gerd Techow was arrested the following day, and Ernst Werner Techow, who was visiting his uncle, was taken into custody three days later. Fischer and Kern, however, remained on the loose. After a daring flight, which kept Germany in suspense for more than two weeks, they were finally spotted at Saaleck Castle in Thuringia, whose owner was a secret member of the Organisation Consul. On 17 July, they were confronted by two police detectives. While waiting for reinforcements during the standoff, one of the detectives fired at a window, unknowingly killing Kern by a bullet in the head. Fischer then took his own life.[27]

When the case was brought to court in October 1922, Ernst Werner Techow was the only defendant charged with murder. Twelve more defendants were arraigned on various charges, among them Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst von Salomon, who had spied out Rathenau's habits and kept in contact with the Organisation Consul, as well as the commander of the Organisation Consul in Western Germany, Karl Tillessen, a brother of Matthias Erzberger's assassin Heinrich Tillessen, and his adjutant Hartmut Plaas. The prosecution left aside the political implications of the plot and focused upon the issue of antisemitism.[28] Before his assassination, Rathenau had been the frequent target of vicious antisemitic attacks, and the assassins had also been members of the violently antisemitic Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund. According to Ernst Werner Techow, Kern had argued that Rathenau had to be murdered because he had intimate relations with Bolshevik Russia and had even married his sister to the communist Karl Radek – a complete fabrication – and that Rathenau himself had confessed to being one of the three hundred "Elders of Zion" as described in the notorious antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. (Ernst von Salomon later claimed that Kern's argument was merely a pretext. Historian Norman Cohn believes that Techow's evidence stands.)[29]

The defendants vigorously denied that they had killed Rathenau because he was Jewish.[30][31] The prosecution was unable to fully uncover the involvement of the Organisation Consul in the plot. Tillessen and Plaas were convicted of non-notification of a crime and sentenced to three and two years in prison, respectively. Salomon received five years imprisonment for accessory to murder. Ernst Werner Techow narrowly escaped a death sentence when, in a last-minute confession, he managed to convince the court that he had acted only under the threat of death by Kern. Instead he was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for being an accessory to murder.[28]

Initially, the reactions to Rathenau's assassination strengthened the Weimar Republic. The most notable response was the enactment of the Law for the Protection of the Republic, which took effect on 22 July 1922. It set up special courts to address politically motivated violence, established severe penalties for political murders and gave government the authority to ban extremist groups.[32] As long as the Weimar Republic existed, the date 24 June remained a day of public commemorations. In public memory, Rathenau's death increasingly appeared to be a martyr-like sacrifice for democracy.[2]

The situation changed with the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. The Nazis systematically wiped out public commemoration of Rathenau by destroying monuments to him, closing the Walther-Rathenau-Museum in his former mansion and renaming streets and schools dedicated to him. Instead, a memorial plate to Kern and Fischer was solemnly unveiled at Saaleck Castle in July 1933, and in October 1933, a monument was erected on the assassins' grave.[33]

The Nuremberg U-Bahn station Rathenauplatz is not only named after him but also bears his face in portrait along the walls.

Fictional portrayals[edit]

Rathenau is generally acknowledged to be, in part, the basis for the German noble and industrialist Paul Arnheim, a character in Robert Musil's novel The Man Without Qualities.[34] Rathenau also appears as the ghostly subject of a Nazi seance in a famous scene in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow. In 2017, the events and aftermath of Rathenau's assassination were depicted in the first episode of the National Geographic series Genius.

Works[edit]

- Reflektionen (1908)

- Zur Kritik der Zeit (1912)

- Zur Mechanik des Geistes (1913)

- Von kommenden Dingen (1917)

- Vom Aktienwesen. Eine geschäftliche Betrachtung (1917)

- An Deutschlands Jugend (1918)

- Die neue Gesellschaft (1919) The New Society translated by Arthur Windham, (1921) New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

- Der neue Staat (1919)

- Der Kaiser (1919)

- Kritik der dreifachen Revolution (1919)

- Was wird werden (1920, a utopian novel)

- Gesammelte Schriften (6 volumes)

- Gesammelte Reden (1924)

- Briefe (1926, 2 volumes)

- Neue Briefe (1927)

- Politische Briefe (1929)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Antisemitic parties included the Christian Social Party, Antisemitic League, Social Empire Party, German People's Union, German Reform Party, German Antisemitic Union, Antisemitic German Social Party, Antisemitic People's Party, United Association of Antisemitic Parties, German Fatherland Party, and German Socialist Workers' Party.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "The Idea of Europe". The Last Europeans. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ a b Sabrow 1996, pp. 336–337.

- ^ a b c d Albrecht, Kai-Britt; Eikenberg, Gabriel; Walther, Lutz (14 September 2014). "Walther Rathenau 1867–1922". Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Ezra; Cohen, Richard I.; Hoffman, Stefani (2014). Against the Grain: Jewish Intellectuals in Hard Times. Oxford; New York: Berghahn Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-782-38003-0.

- ^ Dallas 2000, p. 303.

- ^ Naranch, Bradley D. (September 2000). ""Colonized Body", "Oriental Machine": Debating Race, Railroads, and the Politics of Reconstruction in Germany and East Africa, 1906–1910". Central European History. 33 (3): 299–338. doi:10.1163/156916100746356 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dernberg, Bernhard; Rathenau, Walther (2019). East, John W. (ed.). "Dernburg and Rathenau on German East Africa: Official Reports on a Study-Tour through Colonial Tanzania in 1907". Academia.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (November 2012). "Prophet in a Tuxedo". London Review of Books. 34 (22).

- ^ Volkov 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Wehler 1985, p. 106.

- ^ Fink, Carole (Summer 1995). "The murder of Walther Rathenau". Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought. 44 (3).

- ^ Rathenau, Walther (1918). An Deutschlands Jugend [To Germany's Youth] (in German) (Project Gutenberg ed.). Berlin: S. Fischer Verlag. p. 9.

- ^ Wehler, p. 160

- ^ "Walther Rathenau, "Hear, O Israel!" (1897)". GHDI (German History in Documents and Images). Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Asmuss, Burkhard. "Die Kriegsrohstoffabteilung". www.dhm.de (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Wehler 1985, p. 235.

- ^ Volkov 2012, p. 179.

- ^ Dallas 2000, p. 517.

- ^ Sabrow, Martin (2003). "Rathenau, Walther". Neue Deutsche Biographie 21 (in German). pp. 174-176 [Online-Version]. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Simkin, John (September 1997). "Walther Rathenau". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Sabrow 1994, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Sabrow 1994, pp. 146–149.

- ^ Sabrow 1994, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Kellogg, Michael (2005). The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Russians and the Making of National Socialism, 1917–1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15, 166, 176–179. ISBN 978-0-521-84512-0.

- ^ Sabrow 1996, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Küppers, Heinrich (1997). Joseph Wirth: Parlamentarier, Minister und Kanzler Der Weimarer Republik, [Joseph Wirth: Parliamentarian, Minister and Chancellor of the Weimar Republic] (in German). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 189. ISBN 978-3-515-07012-6.

- ^ Sabrow 1994, pp. 91–103.

- ^ a b Sabrow 1994, pp. 103–12, 139–42.

- ^ Cohn, Norman (1967). Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 145–146.

- ^ Sabrow, Martin (1999). Die verdrängte Verschwörung: der Rathenau-Mord und die deutsche Gegenrevolution [The Repressed Conspiracy: the Rathenau Murder and the German Counter-Revolution] (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. p. 184. ISBN 978-3-596-14302-3.

- ^ Sabrow, Martin (1998). "Die Macht der Erinnerungspolitik" [The Power of the Politics of Memoryt]. Die Macht der Mythen: Walther Rathenau im öffentlichen Gedächtnis: sechs Essays [The Power of Myths: Walther Rathenau in Public Memory: Six Essays] (in German). Berlin: Das Arsenal. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-3-931-10911-0.

- ^ Jackisch, Barry A. (2016). The Pan-German League and Radical Nationalist Politics in Interwar Germany, 1918–39. London: Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-317-02185-8.

- ^ Martin Sabrow (1998), "Erstes Opfer des "Dritten Reichs"?", Die Macht der Mythen: Walther Rathenau im öffentlichen Gedächtnis: sechs Essays, Berlin: Das Arsenal, pp. 90–91, ISBN 978-3-931109-11-0, retrieved 28 July 2012

- ^ Pächter, Henry Maximilian (1982). Weimar études. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 172 f. ISBN 978-0-231-05360-0.

Secondary sources[edit]

- Brecht, Arnold. “Walther Rathenau and the German People.” The Journal of Politics 10, no. 1 (1948): 20–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2125816.

- Berger, Stefan, Inventing the Nation: Germany, London: Hodder, 2004.

- Dallas, Gregor (2000). 1918: War and Peace. London: John Murray..

- Felix, David (1971). Walther Rathenau and the Weimar Republic: The Politics of Reparations. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-3553-4.

- Gilbert, Sir Martin, The First World War: A Complete History (London, 1971)

- Henderson, W. O. (1951). "Walther Rathenau: A Pioneer of the Planned Economy". The Economic History Review. 4 (1): 98–108. doi:10.2307/2591660. ISSN 0013-0117. JSTOR 2591660.

- Himmer, Robert (1976). "Rathenau, Russia, and Rapallo". Central European History. 9 (2): 146–183. doi:10.1017/S000893890001815X. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 4545767. S2CID 145269033.

- Kessler, Harry (1969). Walther Rathenau: His Life and Work. New York: Fertig. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Kollman, Eric C. (1952). "Walther Rathenau and German Foreign Policy: Thoughts and Actions". The Journal of Modern History. 24 (2): 127–142. doi:10.1086/237497. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 1872561. S2CID 153956310.

- Pois, Robert A., "Walther Rathenau's Jewish Quandary", Leo Baeck Institute Year Book (1968), Vol. 13, pp 120–131.

- Sabrow, Martin (1994). Der Rathenaumord. Rekonstruktion einer Verschwörung gegen die Republik von Weimar (in German). Munich: Oldenbourg. ISBN 978-3-486-64569-9. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Sabrow, Martin (1996). "Mord und Mythos. Das Komplott gegen Walther Rathenau 1922" [Murder and Myth. The Plot Against Walther Rathenau 1922]. In Demandt, Alexander (ed.). Das Attentat in der Geschichte [Assassination in History] (in German). Cologne: Böhlau. ISBN 978-3-412-16795-0.

- Strachan, Hew, The First World War: Volume I: To Arms (2001) pp. 1014–1049, on Rathenau and KRA in the war

- Volkov, Shulamit (2012). Walther Rathenau: The Life of Weimar's Fallen Statesman. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17847-0.

- Struve, Walter. Elites Against Democracy: Leadership Ideals in Bourgeois Political Thought in Germany, 1890-1933. Princeton University Press, 1973. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x11bp.

- Wehler, Hans-Ulrich (1985). The German Empire 1871–1918. Oxford: Berg.

- Williamson, D.G., "Walther Rathenau and the K.R.A. August 1914 – March 1915", in Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte (1978), issue 11, pp. 118–136.

Primary sources[edit]

- Vossiche Zeitung – a newspaper

- Tagebuch 1907–22 (Düsseldorf, 1967)

- Count Harry Kessler, Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918–1937) Grove Press (New York, 1999)

- Rathenau, W., Die Mechanisierung der Welt (Fr.) (Paris, 1972)

- Rathenau, W., Schriften und Reden (Frankfurt-am-Main, 1964)

- Rathenau, W., The Sacrifice to the Eumenides (1913)

- Walther Rathenau: Industrialist, Banker, Intellectual, And Politician; Notes And Diaries 1907–1922. Hartmut P. von Strandmann (ed.), Hilary von Strandmann (translator). Clarendon Press, 528 pages, in English. October 1985. ISBN 978-0-19-822506-5 (hardcover).

Further reading[edit]

- "Rede: 100. Jahrestag der Ermordung von Walther Rathenau". Der Bundespräsident (in German). 22 June 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

External links[edit]

- Walther Rathenau Gesellschaft e. V. (in German)

- Works by Walther Rathenau at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Walther Rathenau at Internet Archive

- Works by Walther Rathenau at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Speech by German President Friedrich Ebert at Rathenau's burial (in German)

- Newspaper clippings about Walther Rathenau in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Walther Rathenau

- 1867 births

- 1922 deaths

- Assassinated German diplomats

- Assassinated German politicians

- Assassinated Jews

- Businesspeople from Berlin

- Engineers from Berlin

- Deaths by firearm in Germany

- Foreign ministers of Germany

- German anti-communists

- German Democratic Party politicians

- German male writers

- German nationalists

- German science fiction writers

- German terrorism victims

- Government ministers of Germany

- Jewish German politicians

- Organisation Consul victims

- People from Steglitz-Zehlendorf

- People from the Province of Brandenburg

- People murdered in Berlin

- Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion

- Weimar Republic politicians

- Writers from Berlin

- 1922 murders in Germany

- 1920s murders in Berlin

- Politicians assassinated in the 1920s